*

TYPES OF PHILOSOPHY

The reader should be able to derive some benefit from the tool kit provided by the geometry of meaning. Geometry and the physical sciences are technical methodologies for control of physical objects. The geometry of meaning is also a technical methodology, but the objects it deals with are mental. By means of it we can keep our bearings in the face of the sophistry, evasions, and ambiguity which clutter the "educated" mentality.

"Mind is the slayer of the real," says the Zen Buddhist. "Therefore, we must slay the slayer." No, mind can serve us well, if it is made to do so and kept in its proper place.

How? By recognizing first that mind, even in the broadest sense, deals only with one aspect of the whole. It deals with relationship; it cannot and does not replace action, nor does it touch on that aspect of the whole that we are obliged, for lack of a better word, to call states (see beginning of Chapter II). Moreover, relationship is itself of four types. Only one or possibly two are properly called mental.

We have, in following Cassirer, witnessed the confusion to which reason can lead. Let us now attend to some of the great problems that philosophy exhibits, much as an art museum exhibits great paintings.

Earth versus Air

This may also be expressed as sensation versus Intellect. As Will Durant puts it, "[the Greek Sophists said that knowledge] comes from the senses only . . . truth is what you taste, touch, smell, hear, see. What could be simpler? But Plato was not satisfied: if this is truth . . . the baboon, then, is the measure of truth equally with the sage . . . Plato was sure that reason was the rest of truth, the ideas of reason were to the reports of the senses what statesmen were to the populace, unifying centers of order for a chaotic mass."*

*The Mansions of Philosophy (p. 26). New York: Simon and Schuster, 1929.

One would think Plato could have settled this issue once and for all. But then we have Locke, two thousand years later, credited with having discovered that knowledge comes from the senses.

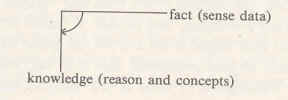

From the point of view of the geometrization of meaning, or

of the four elements, sensation supplies isolated instances (objective particulars) which intellect generalizes to create

concepts (objective generalities).

The shift from the category of facts or particular events to that of concepts is represented as a right angle, analogous to the shift from position (which we detect with the senses) to velocity (which we have to compute by observing a change in position and dividing by the elapsed time), a procedure that is carried out by the mind (the computer-type activity of mind, called intellect).

This aspect of existence, the interrelationship of facts that can be mapped, computed, or communicated, is that available to the Laplacean intelligence. Its objectivity and computability give this aspect its special sanction in Western thought. But, as Cassirer said, "It is but a limited and partial aspect of the totality of being, of genuine reality."*Ibid., p. 4. (Despite this renunciation, we find Cassirer falling back into the trap when he later comes to uphold the findings of the theory of relativity, for relativity makes claims similar to those of the Laplacean intelligence in that it dismisses other kinds of knowledge.)While the claims for objective knowledge are correct as far as they go, objectivity by itself is insufficient even for theoretical computation, which involves a projection from what is given to something else.

Water

Such projection is a category of knowing which takes many forms. We study the rhythm of the tides and "project" for the future. We study a company and project its future earnings, so that no matter how objective we are, we can make no use of this information without projection, that is to say, without assumptions. Assumption or belief is in a different category (water*) than the two categories we have considered so far (facts, or earth, and concepts, or air), a category we call general projective.

*To resort to an altogether different kind of thinking, water symbolizes belief because there is a certain wetness about credulity; water suggests involvement, getting one's feet wet, being in the swim, etc.

This is a difficult category largely because, unlike the general objective, it is neither communicable nor even definable (it is two right angles from fact).

Despite its indefinability and its opposition to fact, we must recognize that it is the belief category that makes a thing real. We recall Hume's statement that causality is a "belief," and one that we are unable to give up. It is this very compulsiveness that carries the conviction of, reality. We have already indicated that it is the basis for experience, to which it contributes feeling (as we feel acceleration, for instance).

This is the knowing which Kant distinguishes as prior to objective experience, calling it transcendental. His description of it as a priori confirms our insistence that it is ontologically prior to objective knowledge.

While Kant regards this transcendental knowledge as epistemological, we have been at pains to show that it is more than that; it is ontological. Thus energy and time exist, but are not objective. If you want to drive yourself crazy, try to think of time as objective. We say, "Give me time," but the transaction does not involve handing anything over. Likewise, energy is not objective in any sense of its being a definable object or having identity. Yet it is real, like pain, acceleration, fear.

The reader may find that he cannot go along with my statement that energy is not objective. "Surely," he will say, "the energy is 'out there' and therefore objective." This I would not dispute, if by "objective" you mean "out there." The designation "objective," however, is generally used in the sense that a statement is objective if it can be confirmed by other people; an entity is objective if it can be seen by more than one observer.

Is time of this nature? Can the present moment be identified? If we say that when the bell strikes, it will be 10:00 P.M., we are identifying a moment in time, but when this moment occurs, it can never be experienced again. It cannot be summoned up for examination as one could a true object. The question of "out-there-ness" becomes meaningless about time. First it is in the future, suddenly it becomes the past. "It" has changed. What is the consistent part that would give it identity?

Energy, which conforms in every respect to substance, the prima materia of philosophers, also lacks the fixed character which would make identification possible. For example, it is not possible to say: "This kilowatt is moving through the wire and lights the book I read." When we measure a current of electricity on an ammeter, we are observing the effect of the current, not the current itself. But that, it might be claimed, is all we can expect.

Well, if that is all we can expect of objectivity, why can't I say my headache is objective because anyone can observe me holding my head and groaning? No, you do not feel the headache as I do. Similarly, the reality of electricity can be experienced if we take hold of the wire and get a shock. When we do this, it is not "out there," it is right here.

This is the special character of the nonobjective "level." We can say that it is out there, but to confirm the "out-there-ness," we must experience it right here, and we cannot erase the difference between this "reality" and "objectivity" by redefining words.

We are thus brought to a rather drastic revision of our view of the universe. We cannot insist that it be exclusively objective. The universe is also projective (or even subjective). This is not idealism or solipsism. The projectivity is not in me, it is in the universe. The universe is thinking or feeling itself into existence!

Fire

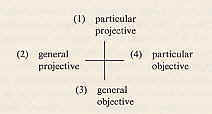

This takes us back to level I, the projective particular. We have placed "photons" here, by which we imply all electromagnetic radiation. This level, of course, has a correspondence to purpose, for this correlation was the basis of Chapter IX on purposive intelligence and the twofold operator.

Taking our cue from the interdependence of free will and purpose (purpose implies free will, and vice versa), we can put free will at this level. Since photons (at stage one) are quanta of indeterminacy, we thus have free will associated with indeterminacy.

What do we mean by indeterminacy? Indeterminacy is, of course, not a concrete thing or object. It is a bit like time in the expression, "Give me time." "Give me indeterminacy or give me death!" Death would be total determinism. "Dead men tell no tales." The opposite of death and determinism is life at liberty: indeterminism.

Let us return to Cassirer. His final rejection of indeterminacy (as equivalent to freedom) reads:

"None of the great thinkers . . . ever yielded to the temptation to master them (the problems of free will) by simply denying the general causal principle and equating freedom with causelessness. Such an attempt is not to be found in Plato or Spinoza or Kant.. ."*Ibid., p. 203.

There are a number of ideas in this statement which we must untangle. In the first place, the thinkers mentioned did not know about quantum physics, and it is quantum physics that cuts through the double talk and forces the recognition of uncertainty.

Secondly, "by simply denying the general causal principle and equating freedom with causelessness" - are we to understand that by this Cassirer means denying cause and effect? I see no need to deny cause and effect - unless by "the general causal principle" Cassirer means the edict against first cause implicit in determinism. But surely he does not mean that. There are many great thinkers who accept first cause. Even stuffy old Aristotle listed final cause as one of the four sorts of cause.

"And equating freedom with causelessness." I cannot see the relevance of this except as an indication that Cassirer is confusing the initial spark with the train of causation that follows in its wake.

Let us take another example. Suppose someone drops a lighted match on the dry leaves of a forest, and in short order there is a forest fire. We say the act was malicious or careless, and blame the miscreant. We would join with the moralist and condemn such freedom as "lawless behavior." I think this sentiment has intruded in Cassirer's analysis of the problem.

But there are several confusions here. While we condemn such action morally, we cannot deny that it is possible. Quantum theory, in fact, affirms it. Moreover, spontaneous combustion does occur, and if we could by act of law prevent all spontaneous occurrences, we would exclude all good acts too. In fact, the moral issue can exist only if there is this possibility of a first cause, the spontaneous act of kindness, the freely given smile. Cassirer knows this and we all know it, just as we know that Achilles can catch the tortoise. The problem is to answer the thought-stopping rationalism that says everything must have a cause. What causes first cause?

What quantum physics offers is testimony from the hard sciences that first cause is. It is everywhere (for example, mutation caused by cosmic rays). It is not so much that ethics must stoop to pick up the crumbs of the scientific banquet, as that the determinist must be made to do his sums properly and not misquote science.

The other confusion is that at no time has it been suggested, either by quantum theory or advocates of free will, that the laws of nature be set aside. No one is advocating causelessness. For it is precisely because free will occurs in an orderly universe that it can have far-reaching effects. If my will says "Forward!" and my legs are paralyzed, nothing happens. If the captain gives an order but the crew stages a mutiny, the captain's will is ineffectual. So we must see the problem not as free will versus determinism, but as free will plus determinism.We may express this interrelationship somewhat paradoxically. An organism is effective insofar as it is both indeterminate as a whole and determinate in its parts. In other words, if all the parts are completely reliable and their actions determinate, the whole functions perfectly. If the whole functions perfectly and is operated by a free will, it cannot be predicted.

This is the answer to the computer stalemate, the problem of two equally matched opponents, both with perfect computers, A and B. Both have complete information and each can anticipate the other's moves. Now provide a random switch at the "top" of A and not at the other. A can anticipate B, but B cannot anticipate A. The random switch puts "life" into A. B remains an automaton, responding but not initiating.

Now, suppose B says, "Ah! I'll go A one better. I'll put two random switches!" What happens? The first switch goes into place at the "top," as with A, but the second must go somewhere else. This means that part of the organization separates out from the rest of the command. It becomes autonomous, and the net result is to weaken B.

Thus unity is very important to freedom of will. Without it we have divided action (civil war, mutiny, disease, paralysis). If we get millions of random switches, we get utter stasis: the vase on the mantle contains billions of molecules moving and vibrating, but the vase stands still.

This bears out a final point of great importance. The ideal freedom, or indeterminacy, which is freedom of the whole, is particular (and, of course, projective).

This rounds out the scheme. It shows that the particularity or uniqueness at 1 is indispensable. This characteristic of 1 emerges from other considerations. For example, it reflects the quantumicity, wholeness, or oneness of action. (Note that 1 and 4 deal with quanta. The quanta at 1 are quanta of action; the quanta at 4 are quanta of matter, molecules. The fact that atoms do not naturally occur in isolation may be significant. Molecules do occur singly, as in gases, or in ordered configurations, as in crystals, or singly again, as in DNA.)

Yet these technical considerations hide the special magic of this final category or aspect of action. To the ancients it was fire, but more in the sense of a spark that initiates; it is the creative, the divine spark, the spirit itself. This is higher mind, intuition. (Note again that intuition is particular; it guesses the exceptional; it does not work by rule, as does the lower or rational mind.)

Naturally, there is confusion about all these points. Cassirer, whose statement we have been trying to untangle, brings in intuition in the end:

"Freedom (means) . . . determinability through the pure intuition of Ideas, determinability through a universal law of reason that at the same time is the highest law of being, determinability through the pure concept of duty in which autonomy, the will's self-ordering according to law, expresses itself; these are the basic criteria to which the problem of freedom is brought back."*lbid., p. 203.

Intuition of ideas . . . universal law of reason . . . pure concept of duty . . . I respect Cassirer's attempt to express the inexpressible, but to me his statement would be improved if he omitted the "push me, pull you" evident in the conflict between freedom and conformity. I prefer to think of this higher type of "determinability" (and by this he means that free decision is effective, that is, determined) as directly opposite in nature to the predictable type of decision that activates the computer.

It responds to a "higher" law, or it responds to its own inner intuition of the future, but it does not react in conformity to the laws that govern and contain secular interchange. If it did, it would comply with the second law of thermodynamics (entropy), and join with molar matter and move lower and lower in the ladder of organization.

ResumeWe have now made our last circuit of the four types of knowledge. Let us enumerate some of the many forms the fourfold divisions of categories take, listing them in reverse order:

Instinct

What is instinct? To call it an innate habit pattern isn't enough. We use the word to cover a rather wide range of phenomena, from the egg-laying habits of wasps to the intuitive hunches of humans that may cover the highest type of creative activity, as when we refer to mathematical intuition.

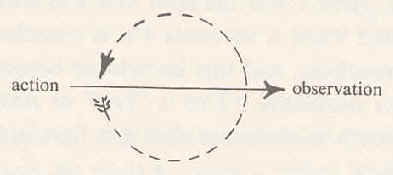

To start with something we can understand, let us take any ordinary action, such as walking, driving a car, speaking, writing, reading. All these activities have been learned by each of us with varying degrees of difficulty. In due course, however, we are able to walk, drive, speak, write, read "instinctively." Whether or not this is like the instinct of animals is not important. The point is that what was once practiced one step at a time and required great concentration becomes automatic and requires no attention; we drive without thinking, carrying on a conversation while we do so. What we have done is to go through the four steps of the cycle of action, until at 4 we learn the proper action which, when it becomes habit,

moves on to 1. Here 1 was the start and was entitled unconscious, and when it succeeds 4 it is conscious, but now it has learned something, and this knowledge becomes unconscious, or instinctive. (This is "fire," or final cause; note that it is final both in the sense that it is first, and in the sense that it is last.)

This is a very interesting thing. We have 1 as both naive and completely informed. Can you "play" the piano? Play chess? Play bridge? A child bangs his fist on the piano; he is playing on the piano. So then he is given piano lessons. He works hard at it. Perhaps ultimately he learns to "play" again, reeling off a Beethoven sonata like a concert pianist. Painting is similar. It is quite easy to turn out a passable sketch. Well, perhaps I'd better go no further, modern art, and all that.

In any case, there is a difference between the stages in the learning cycle, and the difference is greatest between the beginning and the end, even though both are intuitive. We are not forgetting that the cycle may go round and round. A competence which is learned provides the opportunity to undertake a cycle of greater scope. Thus we learn to read, then we read about something, say, integral calculus or quantum physics. This is why instinct is both primitive and complex. This is why intuition is so inexplicable. This is why fire is the category that represents wholeness. As the origin of things, fire is wholeness, wholeness in the sense that an egg is a potential chicken. It is the origin, the seed.

But fire is also the whole when it is regained. It is the whole when the parts have been put back together. And this brings out why mind is "the slayer," as the Zen Buddhist puts it; why mind, which takes things apart, also creates the stasis, inaction, and yet it has to be gone through.

For mind is the midpoint of the cycle of action:

It stands exactly opposite the initial point of starting. It is the point of maximum distraction, separation.

But it would be a mistake to confuse what the mind is for what it does. Mind, though dispersed, converges inwardly. Its opposite, action or fire, though compacted, radiates outwardly. So we cannot pronounce judgment on the elements. We cannot say this is good, that bad. Universal process moves through them all and needs the contribution of each for its fulfillment. "We cannot imagine space extending only to the east," as the Chinese saying puts it.

Becoming

We can make a similar case for the importance of earth and water, for the importance of learning from practical experience, and for the importance of drawing on the deeper yearnings of the soul, whose messages, often in an unknown language, are signaled to us in dreams, in slips of the tongue, in mistaken assumptions by which we twist reality in ways that can be only our own projections.

So we stand, bubbles in the maelstrom of cosmic churning, starting boldly and innocently, receiving rebukes, becoming circumspect, learning carefully, until finally having learned one thing, we launch out again. Life consists of all phases of the cycle of becoming. All kinds of action, experience, and thought have their value. The optimum life does not imply sitting in the dead center, being nothing. It rather teaches that all things have their place and importance, and follow one another, like the rolling of a great wheel.

The Buddhists teach how to escape from the wheel, but I rather think they mean we should escape from endless repetition of the same cycle. Each new cycling should be a new adventure, incorporating, not repeating, what has gone before.

Where does it lead?

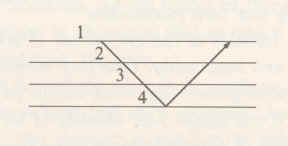

There is only one true escape from the wheel. This is to reverse our direction upon it. To exercise the option afforded by the twofold operator. In terms of the cycle of action, this reversal occurs at control point 4:

It may also be represented, as in Chapter IX, by an arc or V-shape:

In either case, instead of moving counterclockwise from 4 to 1, which would precipitate it into a new involvement, the self makes use of what it has learned to extricate itself by mastering the laws of matter. It turns around and goes the other way.

In Chapter IX we indicated that the grand scheme of evolution followed this V-shaped arc from photons, through atoms, molecules, and cells, to animals and man. But each one of these stages itself involves a process of development, one that goes through stages (which we may call substages in order to avoid confusion with the major stages). Such is the case for man's evolution. According to the Hindus and, to some extent, the West (for example, Plato and Christianity before A.D. 553*), this evolution requires many lifetimes and, according to the scheme suggested by the geometry of meaning, it moves through four levels: first "down," then back "up," the change from down to up constituting man's "rebirth," or self-determined growth to higher status and eventual godhood.

*When the belief in the preexistence of the soul was declared a heresy.

Man's evolution and, for that matter, all evolution, follows, and is closely related to, the scheme of ontology represented in the four levels, but we cannot develop this subject here. Here we have been concerned with ontological and epistemological foundations. As in the foundation for a building, this has involved a great emphasis on the square, the compass, the level, and the plumb bob. It has been primarily a geometrical exercise.

In the last four chapters, we have engaged in a tentative and preliminary exercise by applying the scheme, set out in Chapter X, to human situations.

In Chapter XI, we indicated how steps can be taken toward correcting the piecemeal rationalism of Western thought by invoking the ancient concept of the four elements, followed by a demonstration of the correlation of the zodiac with what we call the Rosetta Stone: the arrangement of the twelve measure formulae of physics in a circular format.

In Chapter XII, we took up a typical philosophical problem, that of free will, using as a reference Cassirer's Determinism and Indeterminism in Modern Physics. Our endeavor here was, again, to show the use of square and compass to deal adequately with the ineffable and necessarily irrational aspect of existence.

In Chapter XIII, we went still further to indicate the scope of the four elements, or aspects of totality, and their ability to interrelate different schools of philosophy. This chapter closes with the indication that despite the fixity of structural relationship, the circle of meaning is dynamic, the basis for an evolving process.

Not only must we recognize the variety of mutually contradictory qualities which go to make up the whole circle, but we must acknowledge two possible directions for moving around the circle. The first or counterclockwise, direction, is the natural one and carries us deeper and deeper into involvement. The second, or clockwise, direction comes about when, having become involved, we are able to learn the law, put it at the service of the will, and thus evolve to a higher state.

The author

Arthur M. Young, inventor of the Bell helicopter, graduated in mathematics from Princeton University in 1923. In the thirties he engaged in private research on the helicopter, and in 1941 he assigned his patents to Bell Aircraft and he worked with Bell to develop the production prototype. In 1952 he set up the Foundation for the Study of Consciousness, which published the Journal for the Study of Consciousness and in 1972 the book Consciousness and Reality, edited by Arthur Young and Charles Muses. The Foundation has now been superseded by the Institute for the Study of Consciousness, located in Berkeley, California, and dedicated to the integration of scientific thought and the development of a science of mind/body interaction.