*

EVOLUTION APPLIED TO MAN

We may now come to the question of man. While philosophers have recognized that even basic questions of existence issue from man, and organize their studies around human consciousness, the sciences, in their quest for the laws of nature, have bypassed man and seized on those aspects of reality that are subject to law, to the neglect of those that are not. There is, in fact, no true science of man, nor even of life.

This neglect could be attributed to the complexity of life processes, of which recent discoveries in the chemistry of DNA afford a glimpse, but these discoveries, while of great importance, are mere peepholes into a vista of the mystery of organic nature. The claim of biologists that they have discovered the alphabet of life, when we take into consideration that the DNA molecule that constructs a bacterium contains information that would fill a thousand-page volume, only shows how very much more there is to learn.

But the sheer complexity of the phenomenon is not the only reason that life is not reducible to the principles of mechanics and chemistry. We have developed in previous chapters the basic contrast between a cosmology based on deterministic science and one based on freedom. Since deterministic science is based on the presumption that there is a cause for everything and a predictable outcome, it cannot, by its own tenets, accept free will as a basic ingredient. Purpose and motive must be excluded. Clinging to this principle denies science access to a recognition of life's essential dynamic, by which it thrusts not only against the flow of entropy, but also against any restraint, and creates exuberant variety where necessity would at best maintain a monotonous repetition.

The same criticism could be applied against the much overrated principle of the survival of the fittest which is a valid principle to be sure, if not a tautology, for it is certainly necessary that life survive.

But it is an inadequate principle, because the necessity that life survive does not account for the initiation of new forms, for life's continuous exuberance, and its evolution from simpler to more complex.

This brings us to the importance of introducing uncertainty or freedom as the basic constituent of existence. Thanks to quantum theory, this can be done without any basic change in the structure of science, for quantum theory has already introduced the needed reform and, starting with protons and electrons, has pushed the application of quantum principles into the interpretation of molecular bonds. Such bonds were once thought of as static hooks or attachments between molecules. Quantum theory, in contrast, sees the molecular bond as a very active engagement involving electron exchange, resembling two dogs fighting over a bone, rather than a joint held by glue. Important to this exchange phenomenon is its frequency, which establishes a cycle of action. Such a cycle of action makes plausible our speculative guess as to how life begins: that by control of timing the quantum of action is able to build order against the flow of entropy, and so initiates life at the molecular level. The cycle of action, as we have explained, is consciousness.

Specific problems of man

But from the molecule on, we lose sight of the quantum of action, and therefore have no endorsement from physics. Nevertheless, we see life evolving through plants and animals to man. With man, we have testimony of a different sort, our direct subjective sense of freedom of choice. True, this freedom is questioned, but by whom? By the determinist, who speaks with a conviction that is allegedly based on the absolute rule of scientific law. He is apparently unaware that this absolute rule of law was deposed some time ago by quantum theory. Nevertheless, his conviction still stands. Based on what? On rational grounds. Here we refuse to get embroiled; the rationalist is impervious to evidence. Let him go. Perhaps he will eventually discover that he is caught in a circular argument.

The difficult problem is not to prove free will, but to answer the question: how is the monad, a fundamental spiritual principle, modified? In what respect is the "elan" of an animal more evolved than that of a plant or a molecule? The question is difficult, if not impossible, to answer because we are not in the realm of things - i.e., objects that have definite properties. The elan, spirit, or monad is not so much a "thing" as it is a power - and it has no measure other than its competence.*

*If we assume that the equation ExT = h (Energy times Time equals Planck's constant) bolds throughout the are, and that the time increase in the second half is the same as in the first half, we would have a period of about 1/10 of a second for human consciousness, close to the alpha rhythm. The time span required to bear a musical note (beats slower than sixteen per second) is close to the beta rhythm. When these are higher-frequency, more than sixteen per second, the result is a sound (low hum). So too with less than sixteen frames per second in a motion picture, the illusion of motion disappears. However, according to the formula ExT = h, this lengthening of time would be accompanied by a billionfold reduction in energy, which seems quite unreasonable. We are accustomed to references to the still small voice of conscience, but surely it is not that small! I am unable to suggest an answer to this problem - except that perhaps, for the monad, the question of energy is academic once it has learned to control timing.

Meanwhile, we have the thesis that the universe is process, confirmed by the evidence for large-scale evolution through stages and grades of organization. Moreover, we have new intellectual equipment which includes the recognition of forces and energies that escape the determinist.

We will in this chapter apply this larger view of evolution to man; and we will show how inadequate is the contemporary view of evolution. We will also indicate the need for distinguishing among several kinds or levels of evolution, corresponding to the several vehicles of which man consists - the cellular organism, the animal body, and the spiritual monad. Only the last is of concern to man, because his cellular and animal vehicles have been inherited from prior kingdoms.

In attempting to treat man in a scientifically respectable manner, we maneuver ourselves into the position of an embarrassed suitor popping the question. Our quest is obvious, but the closer we get to it, the more we take refuge in circumlocution. Scientific parlance becomes circuitous when we try to discuss man himself.

But that is what we want to talk about. To do so, we need to go through a number of anterooms and show our credentials to a number of peripheral "guardians of the throne." Our goal is the evolution of the individual person, a topic that science ignores altogether.

The uniqueness of man: dominion

Let us first consider the objection that science might make against creating a different kingdom for man than for animals. Science has classified man as so similar in anatomical structure to apes that he must have a common ancestor. The "anthropoid ape" is so named (from the Greek anthropos, meaning "human being") because of his resemblance to man. Science further supports this view by citing the evidence of fossils for forms of man which were more ape-like than present-day man. There is no questioning the validity of this evidence. Even if man is not descended from apes, he has the body of a vertebrate mammal.

But man is somehow different from animals. We may describe ways in which this difference manifests in his physique: man stands upright, thus freeing his front limbs for countless other uses; his thumb opposes the fingers, making it possible for him to grasp objects; his brain is larger; he is the only animal with buttocks; he is naked; his penis is large (compared with the ape's). Or we may describe a difference in his behavior: he makes and uses tools; he carries weapons; he communicates with his fellows through spoken and written language; he deals in concepts; he reasons and plans; he is self-conscious; he is religious. Such descriptions may be helpful and give evidence that man is equipped to transcend purely animal functioning, but their mere enumeration does not establish the clear categorical difference we require for a kingdom.

What do we require for a separate kingdom? Note that since the kingdoms are cumulative (each one builds on the one before), a common basis is no bar to the distinction between kingdoms. Thus both vegetables and animals are composed of molecules, and animals share cellular organization with vegetables.

But the vegetable acquires a new power in that it is able to build from molecules a complex multicellular organism (it is a manufacturing "plant"). The animal adds the power of mobility. Now it would be beside the point to insist that because the vegetable had a molecular constitution, it was the same as a molecule, or because the animal had a cellular constitution, it was the same as a vegetable. So we can go on to say that man's animal constitution is no bar to a separate status as man.

Nor is this claim made on behalf of human dignity. As a matter of fact, it reads the other way, for as we will show in the next chapter, man in his kingdom is far less evolved than are the vertebrates in the animal kingdom. Man, we repeat, is as far along to his goal of dominion as is the clam to its goal of mobility. (See grid in Chapter VII.)

Since the dominion kingdom is theoretically established by the symmetry of the arc, the assumption to be made is not the existence of the kingdom, but the legitimacy of man's placement there. Be he naked ape or killer ape, we need to discover what it is about man that makes him eligible for membership in a mode of being that transcends the one degree of freedom of vegetable growth and the two degrees of freedom of animal motion. We need to look at the human principle and discover its abstract character.

Emphasis on this abstract character permits us to see the upright stance, the opposed thumb, the greater brain size, the use of tools and of language, and of even deadly weapons, as part of a syndrome, supportive spokes that radiate from the dominion principle. These tools provide not just means for conquering nature but, as is becoming increasingly apparent in modern times, the means for man's own destruction and, hence, a challenge, the challenge to achieve self-control, to attain the responsibility of stewardship.

The animal in man

In fact, viewed in this light, man and his animal heritage are seen to be not only separate, but in conflict, a conflict whose goal is the emergence of a working combination, of mobility and direction; the horse of power must be controlled by the rider. The ancients expressed this partnership in the person of Chiron, the wise teacher, portrayed as a centaur, a creature with the body of a horse and the head of a man. The failure to achieve this state was symbolized by the Minotaur, the monster kept by King Minos in the Labyrinth, which had the head of a bull and the body of a man.

But let us return to observable facts. in the astounding variety of animal shapes as compared with the invariance of man's shape, there is the hint of a difference that is fundamental. The vertebrates alone, from eels to elephants, display enormous variation, whereas man is inevitably the same two-legged, two-armed creature. Of the thousands of species of mammals, the tens of thousands of vertebrates and the hundreds of thousands of species of all animals,* the entire range of mankind occupies but one species, Homo sapiens. In the animal kingdom it seems as though nature is exploring the world of shapes; it is creating a tool kit. It invents a battering ram (a rhino), a prehensile, flexible tube for lifting (elephant), a nibbling machine for cutting down trees (beaver), a drill for getting insects out of trees (woodpecker), a high-frequency sonar device (bat), a detector of infrared radiation (owl), and hundreds of other ingenious forms for coping with the problems of survival.

*Tracy I. Storerin General Zoology (New York: McGraw-Hili, 1951) accounts for 4,400 mammals, 40,600 vertebrates, and a minimum of 800,000 species of all animals.

But when it comes to man, nature changes the emphasis. It makes man a generalized user of tools. This is a shift of an abstract and definite nature, a shift that is just such as is required for a kingdom. Such a shift could not be accomplished (or let us say we cannot conceive of its being accomplished) in any other manner than by settling on some one animal form, and letting this form create the tools that formerly endowed the separate species.

By making a tool a separate thing, man achieves a tremendous advantage. He may wield a club, throw a stone or a spear, put on the fur coat of an animal, even fashion a drinking cup from a horn. In doing one of these special functions, he does not give up the others, nor does he incur the limitations that animals have to put up with in evolving hoofs or claws or tusks. The fantastic variety of bills that birds have developed, which confine them to quite specialized feeding habits, shows that evolution with animals can go only so far.

So man surrenders the more immediate advantage of a special shape or of making his limbs into special tools, and instead uses his otherwise ineffectual hands to fashion tools, weapons, habitations, and vehicles to meet the requirements for survival, but he does even more. He begins to disconnect from intimate partnership with and participation in nature.

This is a dangerous experiment. We are familiar not only with the warnings of the psychoanalyst that man must not cut himself off from his lower nature, but we are now hearing the voice of nature itself, as pollution, poisons, and other side effects of progress make themselves felt.

This warning, of course, must be heeded, but the solution is not in specialization, as it is for animals in the horse's legs and teeth, in the elephant's trunk, the tiger's claw, etc., but in disconnection, not just from machines, but from the habits and "mechanism" of the psyche and even the "mechanism" of society. We should rule mechanisms, not be ruled by them.

This need to throw off compulsive embodiment, to disconnect from specific function, to become universal, a total being, is the role of man. In the ability to use different tools, to function in different ways, he contrasts with the animal, which is committed to one element, to one diet, to one habit pattern, and therefore is that function.

Thus man can have what animals are compelled to be, and man's being is freed to take on greater challenges.

This principle carries the key to the steps of evolution in that each power employs (or has) the power that precedes it, viz.:

Particles have intrinsic freedom (action/light).

Atoms organize nuclear particles (to build atoms).

Molecules combine atoms.

Plants organize molecules (to build cells).

Animals feed on vegetables (as food supply).

Man uses animals.

Man's "use" of animals or of the animal power is not only in the breeding and domestication of actual animals, but in the use of machines to provide mobility and other functions. When he uses horsepower, it doesn't have to be with a horse. In this way man gains the advantage of the specializations to which the animal is dedicated without incurring the penalties. Thus man may ride a horse without giving up his hands; by making an airplane he can fly without the severe anatomical restrictions that the bird must meet.

We thus describe man by contrasting him with animals. We observe that the "being" of an animal is properly expressed through some characteristic mode of behavior: it is fox-like, elephantine, leonine, bearish, ant-like, waspish, worm-like, whereas the being of a man is freed from this specific character. If a man behaves like a mouse, eats like a pig, works like a beaver, he is doing so by option, not by necessity, and because it is an option, he is criticized or praised for his behavior.

This leads, then, to a final and rather difficult fact about man, which is that, while we know perfectly well what people are, there is no common distinguishing characteristic of all people. They are, of course, bipeds, vertebrates, warm-blooded, etc., but this is a heritage which, as we have already argued, is carried over from the animal kingdom, much as animals carry over cellular organization from the vegetable kingdom.

This means that it is impossible to ascribe a specific nature to man. The goal of evolution is that which transcends limitations, and, since to define is to limit, we cannot ascribe definite attributes to man.

The goal of dominion

The dominion kingdom has as its ultimate goal the evolution of unlimited being, ultimately of God, a traditionally ineffable existence, inexpressible, unspeakable, but the notion of God is also synonymous with the supreme absolute, something far beyond man and not pertinent to the intermediate stages of dominion. What is appropriate is the ineffability, for whatever the limitation of characteristics which attaches to a person under specific circumstances, or in a specific action, we may in theory expect that it can be overcome. We expect the person to be capable of being other than or more than he was in the action in question.

I emphasize this point because it is essential to our theory, which anticipates this "open" or unlimited area. The second level* is by nature infinite, as the third is finite. The open and unlimited quality of the first level is not simply infinity in the sense of "without end" (in mass, temperature, energy, etc.); it is doubly infinite. It is infinite "no-thing-ness."

*Particies (or energy) are infinite because they cannot be destroyod; atoms can (atomic bomb).

Rather than struggle to define the undefinable, let us take the opportunity which we now have to know this idea directly. Aside from your body, what are you? What am I? If we find it hard to allow the existence of something that has no qualifications, how can we allow our own existence? If we are a monad that was once in a molecule, in a cell, in an animal - what is this monad? What was your face before your parents were born?

With this preparation, we may now hear the evidence from evolution as it is described in the texts. The following presentation will already be familiar to many readers, but it is my hope to show that it has been put to a number of uses which do it no credit. It has been used as propaganda,* for cover-up, and for rationalization in ways that suggest the errors of which teleology and purpose are customarily accused. Furthermore, and most important in the present context, it has been improperly applied to man.

A resume of showcase evolution*

*To contest literal interpretations of Biblical accounts.

From fossil evidence we know considerable detail about the evolution of a number of animals. Let us take the horse, for example. The evidence for the evolution of the horse from a five-toed ancestor (the eohippus, a creature about the size of a dog) exists in the form of fossils of varying age. It is possible, by placing the fossils in a sequence beginning with the oldest, to find the leg of the five-toed eohippus gradually lengthening and the number of toes reducing.

Eohippus 5 toes

Protorohippus 4 toes

Misohippus 3 toes (side toes touching ground)

Protohippus 2 toes (side toes not touching ground)

Equus 1 toe (splints of 2nd and 4th toes)

Similarly, the elephant has gradually evolved a trunk. Such instances are the "showcase animals" of evolution; it is assumed that other creatures and other functions evolved in similar fashion. But let us note how this evolution takes place. Primarily, it is dependent upon specialization and the usefulness of the specialized members. The horse specializes in running and, as the land rises and food gets scarce, he has to roam farther to get enough food. Presumably, he is set upon by predators and has to be able to escape. Hence, through survival, the modern horse has evolved legs suitable for rapid travel over land, teeth for feeding on grass, etc. At the same time, the capacity to pick up grubs and climb trees, which the less specialized opossum retains, has been sacrificed.

This example of the horse's leg is considered the prototype of all evolution, but it has a number of limitations which read against it as the solution to other evolutionary problems.

To describe the problem of evolution more fully, we must realize that selection is not the only factor. For selection to operate, there must be variation, and the source of this variation has always been a problem. The older naive interpretation assumed that things just naturally varied. The ears of corn varied in length, and if you selected the longest ears for seed, you would get long-eared corn. This is only partly true, for while you can get in this way a greater proportion of long-eared corn, you will not get longer ears than were available in the first place. You have purified the breed, but you've not created anything new. In addition, that mechanism which can ensure the reproduction of millions of generations by its very nature must deny random variation; the rules that would ensure a sound product exclude deviations. The printing press can be expected to duplicate a book, but not to write new books.

In the face of these objections, the Darwinian theory (of evolutionary survival) would have collapsed were it not for the rediscovery of Mendel's law and the modem modified version of De Vries' theory of mutations. De Vries held that the chromosomes themselves could be altered irreversibly by cosmic radiation. Such changes would be transmitted, and while most would be undesirable, some would be desirable. Selection would eliminate the undesirable changes. The survival train was back on the track and running again.

Now I have no wish to discredit this theory of mutation due to cosmic rays. It is probably the correct explanation of many phenomena, and there is no doubt such mutation does occur (not to mention that creation of a new species by mutation due to cosmic rays has a familiar ring, suggesting, one is tempted to say, the Virgin Birth). But to account for all problems of evolution in this way is absurd, and does no credit to science, which on this touchy subject has been more political than scientific.

To see the limitations of using the horse as the prototype for all evolution, let us fill in the picture. We must first grant a gradually changing climatic condition which puts a premium on mobility; there must be a need for the grazing animals to range farther and farther to have enough food. Under such circumstances long legs are an advantage, and each increment in length of leg has survival value. The dog-like five-toed eohippus, over a period of fifty million years, continually pressured by necessity to move about rapidly, evolves into the modern horse.

Now apply this to the evolution of the bird. The bird has a greater task than the horse; it must make a jump to a new kind of existence, live as it were in a different element; it must invent. The eohippus, to become the modern horse, did not have to innovate; he was already running about in search of food, and his evolution into the modern horse was a consequence of doing better what he was already doing. The creature that was to become a bird had to give up the use of two perfectly good feet and dedicate them to evolution into wings. This idiosyncrasy would have had no survival value until the creature could actually fly, and this would have been only hundreds of mutations and millions of years later, for flight depends on a number of simultaneous design changes: hollow bones, increased blood temperature, feathers, and many more. Mutation could conceivably have produced these changes separately, and over a long period of time, but it could not have produced them all at once, unless you believe that monkeys could write Shakespeare. And until all changes had been made, the bird could not fly and hence could not survive better than four-legged competitors. So the evolution of the bird is not just a more difficult kind of evolution; it involves problems which cannot be solved by the mechanism that worked for the horse-increased specialization.

An equally puzzling problem, which a superficial consideration might dismiss as similar to the horse's legs, is the evolution of the human brain.

What makes the brain different from other evolutionary devices for coping with survival is that the brain develops by not specializing. Its value depends on being able to apply the experience gained from one problem to another problem. If the brain evolved by specialization, then children would be born speaking English or knowing solid geometry, just as the horse is born able to walk and run almost immediately. Indeed, the evolution of brain or mind is such a different problem from that of the horse's leg or the elephant's proboscis that it may not fit at all into available niches, and may require the type of evolution which we will discuss at the end of this chapter.

Finally, the most comprehensive shortcoming (if we can use such a term) of the current theory of evolution is that it does not account for jumps to a higher level of organization.* As has been pointed out, there are many examples of creatures, low on the evolutionary scale, continuing to survive after hundreds of millions of years. The horseshoe crab is the most primitive of arthropods, and yet is doing very well. The shark is classed below the true fishes, yet it holds its own despite the evolution of higher forms; and there are thousands of primitive life forms which survive well today. Why then is a leap to higher forms necessary? If it were a case of evolve to a higher level or perish, the lower forms would have dropped out. In addition, the leap to a higher level of organization cannot be explained genetically any more than could the accidental mix-up of parts turn a carriage into an automobile, or a telephone into a radio.

*LeCompte de Nouys makes this point in Human Destiny, New York: Longmans Green & Co., 1947; David McKay, 1947.

The problem presented by those leaps from one level of organization to a higher one is not even considered by current theories of evolution. Its treatment, in fact, takes us right into the theory of process we are presenting. It cannot be studied by examining the details of zoology; it requires a more comprehensive view, one that recognizes the problem of leaps to higher types of organization in other areas, in the development of molecules, or of the shells of atoms (for atoms and molecules, as is evident in the grid, evolve through the same substages of organization as do animals, yet survival of the fittest can hardly apply to atoms and molecules).

To sum up then, there are important respects in which the current theory of evolution (survival of the fittest) is inadequate, and we should invite some new approach. This is offered by our theory of process. We have already (in Chapter XI) indicated how the hypothesis of a group soul would account for instinct, but this does not exhaust the possibilities.

Genetic and instinctive evolution

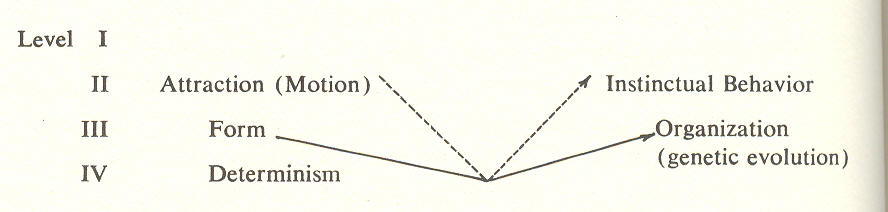

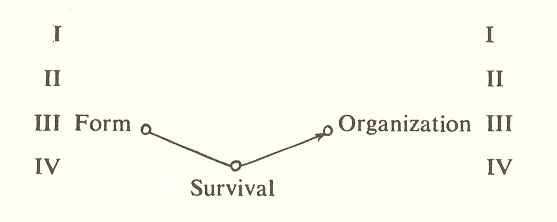

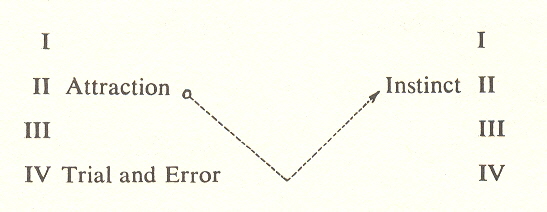

If we return to our four levels and note their relevance to the problem, we can account for at least two sorts of evolution: genetic evolution and the development of instinct.

The problem of any evolution is to achieve control and reach the volitional side of the arc. For genetic evolution this is done by the test of survival, for development of instinct by trial and error. While the former is recorded in the DNA and the latter in the group soul, the proving ground for both kinds is level IV.

The distinction between genetic evolution and instinct could be likened to that between the design of an automobile and the driving habits of the operator. The design evolves as different models succeed one another, self-starters, balloon tires, four-wheel brakes. The driver accumulates experience with the years: he learns turn signals, traffic rules, to anticipate the other drivers' intent, where his friends live, and so on. Both kinds of evolution occur and are necessary.

Group soul

In the last chapter we introduced the concept of a group soul as a hypothesis which would account for a number of inexplicable phenomena, including the elaborate instincts of animals. In this chapter we are emphasizing evolution and will consider the group soul concept along with other theories. Our goal is the evolution of man, but to reach it we have a certain amount of spade work to do.

For example, legitimacy. The group soul concept might be ruled out on the grounds it is inconsistent with scientific principles (whatever these may be), but it is not inconsistent with the theory of process; in fact, it is implied by the theory we are presenting. Even further, I believe it is implied by the basic principles of science.

Because the group soul comes into existence with the animal principle, it is level-II and hence of the nature of an energy which, by the principle of the conservation of energy, cannot be destroyed (as can form, meaning an assembly of parts such as atoms, molecules, or cells).

The group soul concept follows from the theory of process because the theory of process requires that the animal principle be immortal. (Just as science requires that energy be indestructible.)

The group soul concept does not replace genetic mutation, but it can implement it. Applied to the evolution of the horse, the mutations which give rise to long legs could well be assisted by, and might even require, behavior which takes advantage of the long legs (running).

In other cases, such as the termite colony observed by Marais, the group soul is the only explanation. In fact, based on the genes alone, we could not distinguish the queen from the worker termites, or the soldiers from the drones; this differentiation is based on group need, which may be equivalent to what we call group soul. When the queen is killed, a worker termite is given the special food that transforms it to a queen. Since the queen and the other termites - workers, soldiers, and drones - have the same DNA, there are factors other than DNA operating. These depend on the needs of the whole and thus suggest an organizer body which is a kind of group soul independent of its individual members. It is evident that there are new worlds of connection, new additions to science in the possibilities which unfold.

The group soul concept, it might be mentioned, provides a mechanism for the "inheritance of acquired characteristics," alternative to that given by Lamarck, who first proposed such inheritance as an explanation of evolution. His theory is very much out of favor today, primarily because the accepted mechanism of cell reproduction (DNA) cannot account for either the learning or the inheritance of acquired characteristics (acquired characteristics would include behavior learned by trial and error). That is, because the cellular material responsible for sperm and eggs is isolated from the rest of the organism early in life, the behavior of the parent cannot be imprinted on the germ cells and hence cannot be inherited.

This conclusion may prove somewhat hasty, for while it is true that the chromosomes cannot be affected by the behavior of the parent, it is by no means self-evident that the cytoplasm (the cell content that is not in the nucleus, the DNA) could not be affected by the behavior of the parent. In fact, this would be the explanation of recent work which has shown that planaria worms inherit the education of the parents. The inheritance of memory in planaria can be explained as carried by chemical substances. I therefore cannot call on planaria to support the group soul theory, but I can use the example of planaria to illustrate that there are two possible kinds of inheritance: the accepted one attributed to DNA, and another that can account for planaria. The former depends on form (level III) and the latter on substance (level II).

These two principles, form and substance, are so basic to our theory, and so universal, that we can almost make it a rule that where one is, the other is. In the case of planaria, substance is involved in the literal sense that the blood stream carries substance that was once part of the parent. Even more so in the case of young worms fed on worms that had been conditioned to avoid the light. The new worms learn more quickly (to avoid the light). One theory is that the conditioning experience creates molecules which remain in the blood.

Our theory goes further in that it postulates a more ultimate substance, psychic energy, which in animals is the group soul. What the theory cannot say is at what stage in animal evolution the group soul emerges; the very primitive animals, sponges and coelenterates, can hardly be said to have instincts; their mobility is too limited. On the other hand, with insects, colonial insects especially, instinct is elaborate. Ants and bees behave in a way that suggests a highly developed group soul. Thus we must suppose that group soul, like the animal, is evolving; indeed, it would be more correct to say the animal group soul is the animal, and is evolving in conjunction with its vehicle, the cellular organism.

Can we find other support for the group soul concept? I myself was impressed by a small book on the subject written by the theosophist Annie Besant. But the group soul concept has always been part of the tradition of "primitive" people, who, as a matter of fact, are in a far better position than modern man to have a correct understanding of wild animals since their existence depends on it. Having considered various theories which apply to the evolution of animals, we can now ask how they might apply to the evolution of man.

What evolution? How do we know there has been any evolution of man? Granted, of course, that civilizations rise and fall, granted that science and technology have made an increasingly rapid progress in the last two hundred years, granted that more people than ever before are receiving the benefits of education, vaccination, and medication, granted anything you like, equality for women, biodegradable containers, colonies on the moon - has man evolved?

Man's peculiar evolution

For all the discussion of evolution, including the question of man's ancestry, there has been no intelligent attempt to apply the concept of evolution to man himself. Most of the ammunition went to proving man was descended from ape-like progenitors, but so what? Granted that man has an animal body (and we have explained why this does not mean he belongs to the same kingdom, any more than the cellular constitution of animals means that they are vegetables, or the molecular constitution of plants means they are molecules), why should he not be ape-like? In any case, the real issue never seemed to come up.

That is, what effect, what meaning has evolution had for man? There is certainly no detectable difference in human physique in recorded history. Ancient sculptures show that. And though present humanity may have evolved from such characters as are found in the files of anthropology, the Peking man, the Java ape man, the Heidelberg man, and the Neanderthal man, the steps in this evolution are by no means proved, especially since contemporary with some of these was the Cro-Magnon man, who was quite a fine specimen, taller, and rather more handsome, than modern man. Furthermore, had man's evolution been directed toward body changes, it would have produced as many different kinds of body as animal evolution has with the 800,000 species of animals. How can Darwin's theory on the origin of species by means of natural selection have any pertinence to human evolution, when all mankind is but one species?

How then has man evolved and how will he evolve in the future? Body changes not being significant, we might suspect he would evolve a better brain, but has he done so in the past? Are our present philosophers, our writers, our sculptors, better than the Greeks? Our technology may be better, but this is not necessarily because the engineers are more intelligent; it may be because of the cumulative effect of the past.

Weakness of Darwinian evolution for man

We should not overlook the fact that for man the survival mechanism on which Darwinian evolution is dependent breaks down, and goes into reverse! In modern civilization, for example, the most fit tend to have fewer offspring. In fact, in India the more highly evolved individuals in many cases dedicate themselves to a celibate life, and there are other ways in which civilization, by preserving the sick or the mentally unfit, tends to annul the selective factor in man as a species. This again stresses that there is another type of evolution for man as an individual.

The crowning touch is that according to the genetic theory, our struggle with adversity - our wars, our trials and tribulations, our education, our search for truth and for the good - because it does not affect the germ plasm, has no effect on the genetic evolution. It is entirely wasted. In terms of present genetic theory, we might just as well omit civilization, life, work, careers, just put our seed into bottles and send it to the breeder. We ourselves are not even as useful as cattle, who do produce meat and dairy products.

These are not idle speculations; they are the considerations into which we are forced by the stampede to turn the present incomplete notions of science into dogma.

Inadequacy of group soul concept for man

Nor can we do any better by calling on the group soul concept, so helpful for animals, to help in accounting for man. If anything, with man the group soul must be operated against. Man evolves not only insofar as he is able to "break away from the herd," which is our unconscious recognition of the group soul, but also insofar as he "overcomes his animal instincts," that is, goes against the behavior pattern that for the animal would be an optimal if not necessary solution to its survival (see end of Chapter 9).

To get to the problem of man, we must look at humanity not as a species, but as made up of individuals. When we do this, the technical unity of Homo sapiens gives way to great variety. Have you ever known two people exactly alike? I have known several pairs of identical twins whose appearance was so similar it was almost impossible to tell them apart, yet in character they were altogether different, as different in fact as are people who are not identical twins. There are many respects in which people can be alike, sex, color, height, education, cultural background, etc., and twins might be identical in these respects and quite different in their character. It is the latter that we should hold in mind when we are speaking of human evolution. How does a person's total character evolve? The color of eyes, hair, etc., is genetic, inherited in the germ plasm, as are all anatomical details, and we might speculate that the climbing instincts of small boys is an inheritance of the kind of instinct and behavior which becomes important to animals. But how do we account for the unique character traits that make, say, a Mozart?

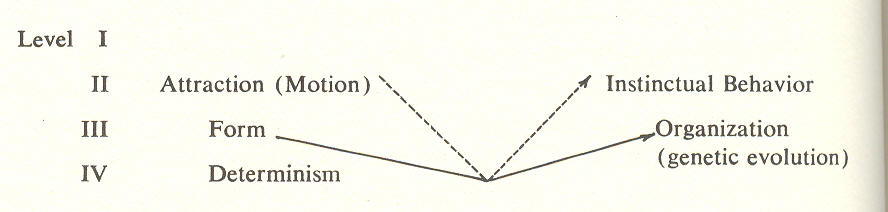

The evolution peculiar to man: the individual soul

Here is where our theory offers a third type of evolution. In plants we have the evolution of the cellular organism traceable to the DNA. In animals there is added the behavioral evolution which is made possible by what we call the group soul. In humans we have a yet different kind of evolution, that of the individual soul.

An individual soul is not a group soul, but like the group soul it is immortal. Like the group soul, its experience is cumulative (the "soul" in both cases is the memory bank drawn from former existence in which lessons were learned), but the individual soul has a different task from that of the group soul. This is to transcend, rather than to repeat or react to, its previous experiences. In other words, the animal is exploring and exploiting to the fullest the way of life that its instincts open up - the beaver builds dams, the anteater confines its diet to ant hills; neither would think of going to a psychoanalyst to get over his mental fixations, or to broaden his education by the study of Sanskrit. Yet man is under an obligation to take on greater challenges; we can even say that he wants new kinds of experience, that he may enjoy a routine for a while, but that it is normal for him to make basic changes during his relatively long (by animal standards) lifetime. The pleasures of being a football player lose their appeal in the mid-twenties at just about what would be old age for a horse.

In another sense, man may stick to one skill for more than one lifetime. For example, Bobby Fischer, like other chess champions, exhibited early in life such an exceptional ability in and inclination for chess that he must have learned chess in previous lives. And note the importance of incentive. Bobby Fischer is highly motivated. Even if we accept what I am stating is impossible, and that chess playing behavior could be transmitted by DNA, DNA could not transmit his powerful incentive - which keeps him continually thinking and dreaming chess, even to wanting to smash his opponent's ego, an issue which would not concern a computer. General Patton is also interesting in this respect not only because of his conviction of previous lives as a general, but because of his courage in publicly stating this conviction.

Against modern opinion, which would rule out not only preexistence of the soul, but the soul itself, one could cite Plato, whose doctrine of the soul's immortal nature was taken over and later questioned by Aristotle. But it is hardly correct to credit Plato with this idea which was general in Egypt three thousand years before Plato drew breath, and is in fact current in most religions, notably Buddhism, Hinduism, and in almost all primitive religion. The soul's preexistence was dropped from Christianity only in A.D. 553 by an edict known as the Anathema against Origen, pushed through by the Emperor Justinian while the Pope was in jail.*

*Head, Joseph, and Cranston, S. L. Reincarnation. New York: Julian Press, 1961; Theosophical Publishing House (Quest Books), 1968.

I confess myself puzzled as to why it suits the Christian church to deny the soul's preexistence; such denial certainly makes the soul's immortality (which the church affirms) less credible, for how can that which doesn't die be born? I rather think that the importance of individuation to modern civilization is the factor that foists upon us this phantasm of a piece of twine that has only one end, the Christian soul. (An endless twine is no more incomprehensible than is time itself.) "For that which is born death is certain," as the Bhaghavad Gita puts it.

Yet we must be careful not to overemphasize the soul. Not only is it subordinate to the spirit (the seventh and first principle), but in a sense it does not yet exist for most persons. We have several times mentioned that man is not very far along in his evolution through the seventh stage, and hence for man soul is second-substage rather than sixth; it is involuntary and unconscious rather than voluntary and conscious as it would become in substage six. This not only accounts for its obliteration in modern life, but is consistent with the most important teaching of Christian religion (and of other religions), the Virgin Birth - but that would take us beyond the scope of this chapter.

What we should complete before closing this chapter is to sketch in what we described as a third type of evolution, one having to do with man.

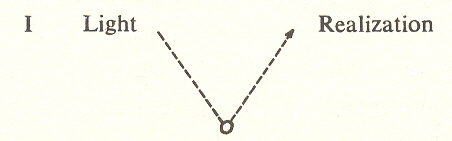

Just as plant evolution requires DNA (level III) and animal requires the group soul (level II), man requires something intrinsic to level I which is almost better described as the divine light than by words such as consciousness or understanding, for it is the light of recognition that leads to the "turn," just as it is the capture of a photon that procures the negative entropy of plants.*

*The capture of a photon by chlorophyll exemplifies the turn, which makes possible the evolution of higher kingdoms on the right of the arc. This should not be confused with the evolution of DNA, which is one step in this evolution, but requires the interaction of three powers: form (to create the drawings), survival (to select the fit), and organization (to manufacture).

The three types of evolution and their dimensionality

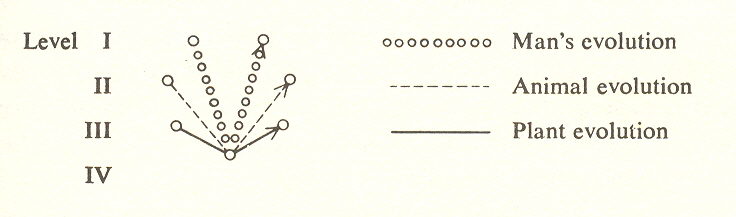

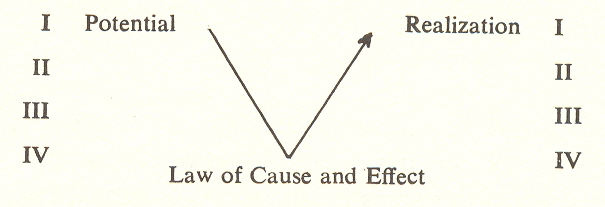

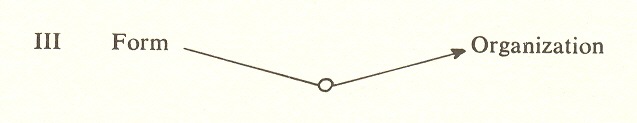

In view of the foregoing discussion, then, we have three types of evolution. First there is the evolution of the genotype, which is effected through DNA. This is the evolution recognized by current science, and produces the cellular organism.

It is an evolution of the design of the mechanism; the blueprint which it starts with as a form at level III (stage three), tried and tested at level IV, and if not eliminated by failure to survive, produces the prototype at level III (stage five).

The process could be likened to the evolution of a mechanical device, an automobile or airplane; the form (level III) is tested at level IV and the feedback evaluated. Where weaknesses are indicated, corrections to the form are tried over and over until it is adequate for production. When this occurs, the process moves on to the organization or growth stage, and a new species comes into existence. This is just how plants evolve, via the cellular organism.

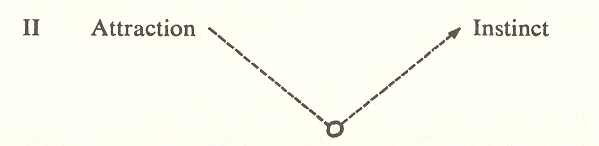

The second type of evolution begins only when there is the possibility of choice, and hence behavior, for without choice there can be no behavior. The behaviorist might deny this, but how does the animal learn to go through the maze? The right choice must be reinforced. A stone, which has no choice, could not be taught to go through a maze. This second type of evolution produces animal instinct. It begins at level II, where attraction causes movement toward or away from the various things in the creature's environment: food, light, warmth, water, other creatures, a mate, etc. Just like the first type (of evolution), instinct is tested at level IV, but its "survival" in this case is better described as trial and error: the creature makes exploratory motions and receives reward or punishment which reinforces the appropriate behavior.

Where the correct choices to achieve the goal have been found, a behavior is learned, and this becomes what we call instinct. There is nothing difficult in this explanation except to account for a way of passing on this instinctual behavior to the progeny. This is impossible by the blueprint mechanism. As we pointed out earlier (Chapter XI), it requires an immortality or conservation of the desire energy of the animal, group soul. The possibility of a group soul is implicit in the notion of the second level, which is such that it does not end in time. Like mass and energy, the "substance" of the second level - which is the "psychic" or desire energy that animates the animal, which in fact is the animal - is evolving in time and does not die with the individual.

The difficulty we have in accepting this notion of immortality arises from the fact that we identify the animal with the cellular organism which does die and could not even theoretically be immortal because it is composite. Of course, the DNA is destroyed when the individual dies, but it survives through the other members of the species. That is to say, the DNA is effective through any member of the species, and for that DNA to die entirely, the whole species would have to be wiped out. Even in such a case, the DNA might survive in seed form; for example, seeds buried in Egyptian tombs thousands of years ago have been found to grow and reproduce.

This raises an interesting idea. Mammoths, a long-extinct species related to the elephant, have been found buried in the frozen tundra of Siberia in such excellent preservation that their flesh is still edible. Perhaps their seed could be fertilized and transplanted to the womb of an elephant to produce a living mammoth. Even if this experiment were successful, we might then find that there was no mammoth group soul to animate the cellular organism.

We are faced with the quite serious challenge of recognizing the animal for what he really is - that an animal is not only a particular lion or zebra, but a representative of the lion or zebra species, and the species is the group soul of that animal which draws on the experience of the species for its inherited instinct and, by its own experiences, adds to the species' experience.

The third type of evolution is possible for man.

This evolution contrasts with that of the animal in that the possibility of understanding the law is added to the trial-and-error syndrome of the animal; this understanding offers the possibility of a much more rapid evolutionary advance. This third evolution is still subject to the need for individual effort, for pain and travail. But it also affords the joys of creative endeavor and the enjoyment of aesthetic sensibilities.

The solution is no longer cloaked in the darkness of inherited instinct which depends (like the mating instinct) on blind obedience to sensory clues that vary with the season; it invites the self to explore the world both of the senses and of the abstract reason, the heights of art, the emotions of love, the discovery of truth.

Like the plant and animal evolution, this third type has its laboratory at the fourth level, where the law of cause and effect affords the opportunity for recognition of truth, for the enlightenment that is the goal of this evolution. Once recognized, the law of cause and effect makes it possible to bring an effect about, to make determinism serve will. Thus the universe is a school in which the monad learns.

Additional information

The dimensionality of the three types of evolution:

Taking advantage of the principles which the theory of process provides, we can supplement the argument just given by reference to the dimensionality which distinguishes the level.

The first, or genetic, type of evolution involves DNA and the cellular organism; initiated in the third level, it is corrected at the fourth. The third level, that of form, requires two dimensions (much as the blueprint requires a sheet of paper).

DNA, it might be argued, is linear. But this is not really the case; though the storage of DNA is linear, much as the magnetic tape which stores a concert is linear, the information is available as it is in a book, to be used at the appropriate time. What we currently know about DNA is only that the information is there; we have not yet learned how the appropriate information is applied at the right time. Thus there is a hidden dimension in DNA, one not yet discovered. If this is not convincing, we have the more basic requirement that any information is two-dimensional, as it defines concepts and operations.

The second type of evolution, the instinctive, occurs at level II. It is an evolution of behavior. Therefore we require time, which is one-dimensional. We have already pointed out that level II deals with values (success is good, failure bad) and values require one dimension only (because more than one dimension would not determine a value unambiguously). We might add that because it is confined to time, the animal is able to form the associations that consolidate its correct choice with an instinct pattern. That is, its successful choice and the reward come at the same time, and therefore the animal associates the reward with the direction of choice.

The third type of evolution occurs neither in two-dimensional space nor in one-dimensional time, nor does it occur in the three dimensions of the physical world, for this (the physical world) is the testing ground of all three evolutions and contains no activity of its own. It is a screen rather than a source; it eliminates the unfit, or verifies the correct behavior.

The third evolution arises at the first level and ends when its goal is achieved. Like the others, it requires the fourth level for its laboratory, but its experimentation does not occur in either space or time. It is instantaneous; it occurs in the present. The present is not a part of time. because it is always the present. Time is the shadow of the present and derives from it.

Now we still need to bring out the peculiar potency of this evolution. Primarily it is recognition, recognition of a principle, realization of a truth, reconciliation of a duality, satori. It is at once the privilege of man, and the formative principle that enables man to evolve. It is an evolution that is realized through man's potential divinity.