*

PROTOPLASM AND PSYCHIC PSUEDOPODS

Having drawn on the evidence from science concerning areas in which phenomena are subject to laws, we should now venture ahead into areas where science has not found laws - or where the only known laws are of a statistical nature.

Process theory and the laws of the four levels

It is generally assumed that all phenomena are subject to law, and that the inability to find such laws is temporary and will be conquered. This presumption still survives in scientific opinion, despite the fact that quantum theory has shown that there are areas in which laws do not hold and cannot in theory apply.

But as was emphasized in Chapter IV, the "fall" into manifestation, by which process gains means for its fulfillment, is necessarily a fall from an initial freedom. This freedom, while random and ineffectual, is the basic ingredient, and law is the means by which process attains the competence to obtain its goals. If we can bring ourselves to think of the determinism of the molecular kingdom as the stepping stone to higher levels of organization and to the recovery of freedom, we can expand our science to cover what would otherwise remain inexplicable. Our theory of process therefore differs from the scientific usage in stressing the importance of freedom as well as of determinism.

Another way in which our method differs from that of science is that we are dealing with individual entities. When we refer to the "freedom" of photons or of fundamental particles, we mean single photons, which, it is correct to say, are unpredictable; or single electrons, which are unpredictable in their position. This would not be questioned by science; in fact, it is a major finding of science. But science, in its emphasis on law, takes refuge in statistical laws or probabilities, much as do insurance companies which predict the percentage of people who will die before eighty, but not which persons will die.

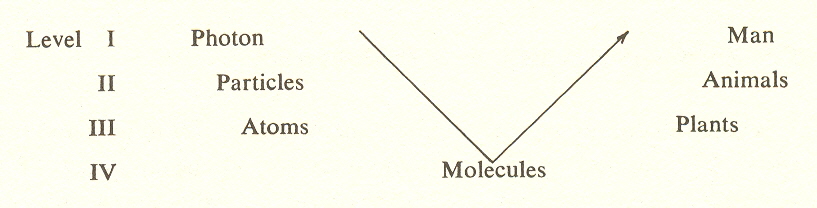

The contribution of the theory of process is that it provides four categorically distinct realms in which law applies in different degrees. These we call the four levels. Level I, with the exception that its photons differ in energy, is free of law. Levels II and III are partially free and partially determined (as described in Chapter IV), level II having two degrees of freedom (position) and level III one degree of freedom (energy). Level IV is completely determined by law. So characterized, the levels describe the principal features of the kingdoms (see Chapter IV).

That is to say, both the growth of plants and the radiation or absorption of energy by atoms are characterized as one degree of freedom, and both the uncertainty of position of proton and electron and that of animals are characterized by two degrees of freedom.

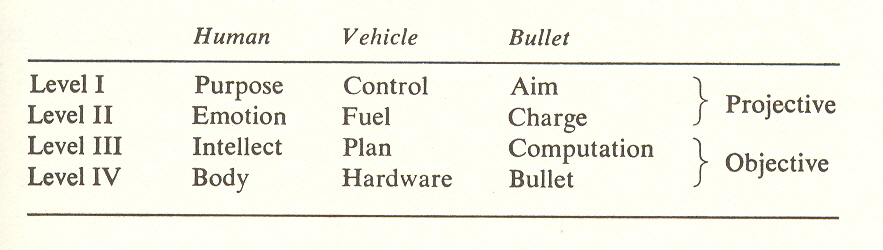

But we are now ready to see these levels in a way that applies more directly to the animal and the human situation. Thus, level I is purpose, level II is motivation, level III is concept formation or intellect, and level IV the physical body, especially in its ability to react to other bodies and thus provide feedback. Of these four levels, the last two (III, IV), are objective: concept formation in the sense that it can be communicated, and the physical body in the sense that it is an object.

It is with the first two that difficulties arise, since both are nonobjective: the photon (or purpose) because observation annihilates it (if the spy's purpose is known, it is annulled), and the nuclear particle because it cannot be identified. Is the electron that came out of the atom the same as the one that went in? Is the dollar I withdrew from the bank the same as the one deposited? Rather than refer to such nonobjectivity as subjective, which would imply that it is interior to the person, I prefer to call it projective, which means only that it is not objective. As we have often stressed, the universe contains this projectiveness. Thus a machine or a vehicle has a projectiveness in its purpose. It must have motivation (the fuel). Similarly, a bullet is aimed (purpose) and propelled by the charge (see Chapter I and also the beginning of Chapter IV).

Our problem is to expand science to include the two projective factors, purpose and motivation, in order to better understand principles which contribute to cosmology and are essential to life.

The phenomenon of motivation

In this chapter we will discuss phenomena which have to do with the second of these factors, motivation, as it occurs in animals and man. These phenomena are of particular interest because of their nonobjective component, which we should no longer have to reject categorically, for we now expect something of a projective nature to exist.

Let us list some of these phenomena:

1. The motion of an amoeba.

2. The emotional projections of persons.

3. The behavioral pattern of animals (instinct).

4. Certain aspects of extrasensory perception.

5. The dream state.

6. The use of sacrifice in primitive religious ceremonies.

7. Psychic healing (by laying on of hands, or at a distance).

8. The ectoplasm of materializing mediums.

I have listed the phenomena in order of the credibility of my use of them from the viewpoint of current rational thinking. It hardly needs saying that some of them are not considered factual, and because they are not, no theory is developed for their explanation. Nor do I ask the reader to credit them all; I ask only that he consider them together.

As to proof, we are in the predicament of having no court of appeal. To take but a single case, the facts of physical materialization by mediums were repeatedly and dramatically confirmed by reputable scientists. Among these is Gustav Geley,* who in 1924 produced casts of ectoplasmic hands interlocked in such a manner that it would be impossible to duplicate by known means.

*Geley, Gustav. Clairvoyance and Materialization. London: Allen & Unwin, 1927.

In order to prove the existence of materializations, Geley made wax molds of hands materialized by the medium. When the wax had hardened, the hands were dematerialized. Geley then poured plaster into the wax mold and, when the plaster had set, melted the wax. (The reverse of the lost-wax process.) He had the testimony of experts that such molds (of folded hands) were such that the hands could not be withdrawn from the mold and were therefore dematerialized (one glance at the photographs confirms this statement).

All necessary precautions against fraud were taken, and some of Geley's experiments were witnessed and testified to by a panel of thirty-four scientists and officials.

More empirical proof can hardly be imagined, yet this work has been totally ignored. Why? Because there is no theory to account for it, and existing theories apparently rule out its reality.

This is but one of many examples, and what is common to each of these examples is that they cannot be explained by modern science.

Schrenk von Notzing also worked with materializing mediums and even captured ectoplasm and examined it under the microscope.** My purpose is not to say that these phenomena have been proved, but to point out that however much proof was or could be provided, the phenomena are not acknowledged as facts because they are so drastically at variance with the prevalent interpretation of science.

**Schrenk van Notzing. A. P. F. Baron. Phenomena of Materialization. Translated by E. E. Fournier d'Albe. London: Kegan Paul; New York: Dutton, 1920.

The criterion of falsifiability

Philosophers of science are given to pontificating at length on what they call the criterion of falsifiability: the thesis that for a theory to be a scientific theory, it must be possible to subject it to test (that might prove it false). It does not occur to them that this weapon might actually be used against the basic postulates of science. Instead, they tend to brand all ESP phenomena as fraudulent on the grounds of being contrary to these postulates of science.* One is reminded of the medieval doctors who denied Galileo's telescopic observations.

*As a matter of fact, I find it difficult to discover what law of science denies the phenomena of telepathy, precognition, etc. It is, rather, with alleged implications of the laws of science that such phenomena conflict.

This attitude is against the interests of true science and is even contrary to elementary justice, for it becomes impossible to correct a theory by experimental test as long as theory decrees in advance what the outcome of the test must be.

The motion of the amoeba

But certain of our listed items to which the hypothesis of an animating and directed energy applies are recognized as facts. One is the amazing instincts of animals (some moths navigate by the stars!). Another is the motion of the amoeba. The latter is one of the simplest facts of animal behavior, yet the amoeba moves without muscles! Actually, motion with muscles in more highly evolved animals only conceals the mystery. What activates the muscles? Nerves, of course, but what activates the nerves?

The following is a typical account of amoeboid movement:

Locomotion is accomplished by forming temporary pseudopodia and is known as ameboid movement. At the beginning of a pseudopodium is a fingerlike projection of ectoplasm (sic) ; then the granular plasmasol flows into the projection as it lengthens. Mast's theory, based upon the colloidal nature of protoplasm, states that the movement is based upon the reversible change from the fluid sol state to the gel state. In this process the posterior part of the moving Amoeba is changed from the plasmagel to the plasmasol, while just the reverse is occurring at the anterior end where the pseudopodium is forming.*

*Beaver, W. C., and Noldand, G. B. General Biology (p. 237). 7th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1966.

This explanation does not tell us what changes the plasmagel to plasmasol, nor how the amoeba can exhibit choice in selecting food. No matter. What happens is observable. The amoeba, described as a mass of dear colorless jelly, forms temporary extensions called pseudopods at any place in the cell body.

Psychic protoplasm

Raymond Prince, in a recent article,* deals with attention and likens psychic energy to protoplasm which is activated and directed by attention. He quotes from Freud, who made a similar analogy between one-celled creatures and libido:

*Prince, Raymond. "Interest Disorders." Journal for the Study of Consciousness, vol. 4, no. 1 (Spring, 1971).

Freud. . . was fond of comparing the ego to an amoeba whose body was in a libidinous reservoir stretching out and withdrawing its libidinous pseudopods as interest was focused and relinquished. In his words:

"Think of the simplest forms of life, consisting of a little mass of only slightly differentiated protoplasmic substances. They extend protrusions which are called pseudopodia into which the protoplasm overflows. They can, however, again withdraw their extensions of themselves and reform themselves into a mass. We compare this extending of protrusion to the radiation of libido on to the objects, while the greatest volume of the libido may yet remain within the ego: we infer that under normal conditions ego-libido can transform itself into object-libido without difficulty and that this can subsequently be absorbed into the ego."*

*Freud, S. A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. New York: Doubleday, 1920.

Let us return again to Geley.

Geley, in 1924 in the introduction to his work, Clairvoyance and Materialization, rejoices in the then current shift to experimentation with mediums and away from "mystical theories." In the reports of the Metapsychic Congress of Copenhagen (1921 ) and Warsaw (1923), he points out "there is no allusion to phantasms of the living and the dead, to spirits, etc. All speak very simply of a biological phenomenon," to which "there appear to be analogies, or at least points of contact, between the ectoplasmic process on the one hand, and normal physiology, animal biology, and certain phenomena classed among the natural sciences, on the other." And he continues:

"Materialisation" is therefore no longer the marvellous and quasimiraculous affair described and commented on in early spiritist works; and for this reason it seems to me desirable to substitute for "materialisation" the term "ectoplasmic form." . . .

What is an ectoplasmic form? To begin with, it is a physical duplication of the medium.

During a trance a portion of his organism is externalized. This portion is sometimes very small, sometimes very considerable - amounting to half the weight of the body in some of Crawford's experiments. Observation shows this ectoplasm as an amorphous substance which may be either solid or vaporous. Then, usually very soon, the formless substance becomes organic, it condenses, and forms appear, which, when the process is complete, have all the anatomical and physiological characters of biologic life. The ectoplasm has become a living being or a fractional part of a living being, but is always closely connected to the body of the medium, of which it is a kind of prolongation, and into which it is absorbed at the end of the experiment. Such is the bare fact considered in itself and apart from certain complications which will all be studied later. It is the naked fact, dissected, so to speak, down to its anatomical and physiological structure. This fact is substantiated, with formal proofs, by the common consent of scientists from all countries.

The objective reality of these forms is proved by photographs taken by flashlight, by their imprints on clay, on lamp-black, and on plaster, and finally, in some most notable cases, by complete casts.

The phenomenon is the same in all countries, whoever the observer or the medium may be. Crookes, Gibier, Sir Oliver Lodge, Professor Richet, Ochorowicz, Professor Moreselli, Dr. Imoda; Mme. Bisson, Dr. von Schrenk von Notzing, Crawford, Lebiedzinski, myself, and others, all describe exactly the same thing.*

*Ibid.,pp. 175-176.

Even this long quote does not do justice to this remarkable book, nor of course to the subject. Schrenk von Notzing describes similar findings in his equally important work.

In short, then, there is confirmation for the existence of an "ectoplasm." The question of what it is I cannot answer. What I am trying to point out is that there is a theoretical requirement, as borne out in Freud's selection of the protoplasmic movement of the amoeba to illustrate the behavior of the psyche, and there is also evidence (as in the phenomenon of materialization) for the existence of a formless and animate substance analogous to the undifferentiated protoplasm of the amoeba.

Such a substance is just about what is to be anticipated deductively in the sixth principle of process. It will be recalled that one of the key words used to indicate the essence of the second principle is substance, and that it has to do with attraction and repulsion, as in electrical charges, but that at the second stage it is not under control. Its controlled version should, and does, occur at the sixth stage where, according to our theory, it supplies the animated principle of animal life.

Permit me now to adduce another quote, this time from an earlier draft of the present book, written at a time when I did not know about Freud's choice of the analogy of the amoeba to the psyche and when its similarity to the ectoplasm of materialization phenomena had not occurred to me.

We can now discern that, so defined, the "animal body" is not necessarily or even partially a physical object as is the physical body, which, of course, belongs to stages four and five. We call hunger a physical urge and, compared with mind, designate it. as more material, more tangible. But compared with a stone, or even with the physical body itself-a "true" physical object - the "animal body" is not objective. It is obviously dynamic, a syndrome of urges, pulls, forces, etc. In the use of the term "field," whose scientific and therefore "objective" implications were discussed in the preceding chapter, we are now in a position to supplement the objectivity with direct testimony. . . . As applied to the animal we could use "field" to describe a sphere of influence or interaction extending beyond the body of the animal that determines the animal's orbit of interest. This is a legitimate tentative use of the word.

Working up from the molecular level we find that at the molecular level there was coincidence of the organizing* principle and the embodiment.

*In this particular passage I used the word "organizing" to cover molecular combination, plant growth, and animal mobility.

At the vegetable level the organizing principle extended sufficiently beyond the physical border of the cells to organize multicellular growth (we do not know how, it might be electrical [Burr, etc.], but the problem we are posing now is not to explain it so much as to recognize that it exists). When we come to the animal kingdom, we must recognize that this organizing principle extends still further, enough to provide a basis for interaction with environment and hence for development of senses and the reach-and-withdraw animal activity. (What I now call animation.)

We arrive at this notion of an organizing field that extends beyond the boundary of the physical body by reasoning about what we know of vegetables and animals. We cannot see or touch this organizing principle. The evidence for it is the creature itself. Like the evidence for a magnetic field, which cannot be seen or touched, the presence of a field is detected by introduction of special materials that the field responds to. Thus we detect a magnet with iron filings or a compass.

This should suffice to show the similarities of amoeboid movement, "psychic protoplasm," and ectoplasm to the postulated sixth-stage "substance," or animating principle, which I was endeavoring to describe before having read Freud or Prince.

Normally, one expects things which exist to be visible, but science has extended existence to include entities like force, charge, energy, which are not directly visible. But the fact that ectoplasm, which we would not expect to be visible, can under certain circumstances be photographed is important to our theory because it emphasizes the physical or substantial nature of the animating principle.

The possibility that ectoplasm can be photographed, although not adding to the credibility of materialization, should not be set aside. The quasi-physical nature of ectoplasm may provide the important clue to understanding the unsolved problem of mind-body interconnection. We should withhold judgment until later, when we know more about it either factually or theoretically.

The need for a medium

Let us return to our list of phenomena which have to do with motivation. Two of the items, the use of sacrifice in religious ritual and psychic healing, provide clues. It will be recalled that the protoplasm in the amoeba extends pseudopods at any point in the body of the amoeba and in any direction toward food particles and the like. Mast's explanation may be a correct account of the mechanism of the movement, but it does not dispel the indication that behind these changes there must be the act of will, attention, or intention, which initiates and directs the pseudopods. A similar act occurs within the psyche, as it does in materialization. Thus the ectoplasm is an agency of intention. It is the passive element through which attention or intention manifests.

I owe to Dr. Oscar Brunler the only explanation I have heard of the reason for animal sacrifice. He held that at the death of the animal, a psychic substance was released which made it possible to communicate with the dead - in the case of the religious ritual, with the ancestors or former leaders of that civilization or tribe. Dr. Brunler, to substantiate his view, called attention to the sexual orgies which follow when there has been a mass execution or when many are killed in battle. The "ectoplasm" released on such occasions becomes available and accentuates sexual energies.

A similar use of ectoplasm, Dr. Brunler maintained, occurs with mediums, who make their own ectoplasm temporarily available to the "spirits" for the purpose of communication.

Even if we withhold judgment as to the validity of this explanation, let us at least note its consistency with the overall theory we have constructed, for in the cases cited, as in others, there is a gap between the directing principle and the physical world. The directing principle requires in all cases a medium for communication or other intercession with the physical universe.

The fact that under normal conditions a living creature activates its own organism and interacts with the environment without visible evidence of any medium being involved does not mean that a medium does not exist. Its existence, in fact, fills just the gap that Freud was describing by his analogy of the psyche to the amoeba.

Dreams

This brings us to another item on our list which we have not yet discussed, dreams, which I believe furnish additional evidence, but this time from the subjective point of view.

In dreams we are cut off from the outer world of the physical senses. It is significant that we are not able to run in a dream when we want to, and that if we do "make our muscles do what we want," we immediately wake up. From this it is clear that the part of the brain that governs motor action and control is minimally functional during the dream state. The act of trying to run causes the cerebellum to be switched on and wakes us up. It also seems evident, from the fact that dreams are often completely devoid of correct associations, that the cerebral cortex, which governs learned association, is not functioning. Durham (whose findings are quoted in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica) made measurements of blood circulation in the brain during sleep and found that circulation dropped almost to zero. More recent work involving the encephalograph and measures of electrical activity of the brain during sleep has been interpreted as indicative of brain activity, but if so it is quite different from waking activity.

Yet in dreams we do have vivid experiences, visual, emotional, even aural. We move, fly, have adventures, anxieties, sexual encounters, ordeals, agonies and ecstasies perhaps even more interesting and varied than those in normal life; and yet these experiences are not due to, and are apparently without even a contribution by, the brain. Indeed, it would appear that the brain functions as a load does on a piece of machinery. It ties it down to a specific function. Take the load off a motor and it "races." Or perhaps we should say the brain regulates and channels the psychic activity which in the dream roams about, like a horse out of harness. Psyche and brain are separate.

Emotional projections

Similar indications arise in the so-called sensory deprivation experiments in which the person being tested is kept in a dark, soundless environment, sometimes suspended in warm water so that he can have no feedback to give a sense of muscular orientation. A few days of this kind of thing produces a raving maniac. The person is invaded with all kinds of wild visions not unlike a "bad trip" with LSD.

This is more evidence to show that we are bathed in a world of imagery that is held in check only by the waking mind.

We say that these phantasms arise in the unconscious, but where and what is the unconscious? What is the "substance" from which these vivid hallucinations are formed? To call them unreal or to say that they arise in the unconscious does not explain them.

And what do we know of how prevalent just such hallucinatory imaginings may be in ordinary daily life? I see across the street the back of a fascinating female creature, quicken my steps to catch a closer glimpse; then as I get closer, or see her turn to look in a store window, I see that my imagination has played me false. The girl is quite homely.

Or, again, we are told by psychologists that the new-born chick does not really have a true perception of its mother. It will follow any object of appropriate size, such as an automated football. This deduction may satisfy the psychologists' instinct for mechanical explanations, but for me it rather suggests that "mother" is a subjective idea, an archetype of the chick world, and that this archetype exists prior to the training of sense experience which will eventually make its contribution, but subsequent to what is subjective, or archetypal.

Such considerations fall into place as giving us an inside view of the activities of this psychoplasm which we may also call imagination. Operationally, it is an animating principle; subjectively, it is populated with archetypal, or "typical," images, which attach themselves to or become associated with external objects and thus motivate their possessor toward or away from these objects.

Nucleation through attraction

But there still remains an important point. Let me quote again from an earlier draft of this present book:

The animal moves - or rather, let us say, chases rabbits. Now it is entirely pertinent to say here that people spend money to see greyhound races, and that the greyhounds are induced to race by a mechanical rabbit that runs around a track in front of them. The fact that the rabbit isn't real makes no difference to the spectators or to the dogs. As long as the dog believes the object bounding in front of him is a rabbit, he runs. Wherein for the dog is the substance? "Faith is the substance." . . .

Here at last we have a clue: the dynamic which motivates the dog "nucleates" as a rabbit, a chase-inducing item having an attractiveness just as a positively charged nucleus has for the electron. Perhaps the Playboy "bunnies" are another example.

In other words, we cannot think of the animal power as only a dynamic. It must nucleate as something. It involves a triplicity of object, act, and anticipation, analogous to our second-kingdom triplicity of mass, motion, and charge. In other words, substance is as much a part of the picture as energy is. In fact, substance is condensed psychic energy.

The notion of nucleation is helpful in the tendency of the plastic substance to "fixate" or jell into an image. This "fixing" for the second stage is the particle itself. For the sixth stage, it is the target animal, the mate, the quarry, or whatever object or image becomes endowed with a charge.

Such tricks hath strong imagination,

That, if it would but apprehend some joy,

It comprehends some bringer of that joy;

Or in the night, imagining some fear,

How easy is a bush supposed a bear!

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Act V, scene I

For man, or for human consciousness, these nucleations are what Jung calls archetypes. They are carriers of a charge, endowed with either negative or positive value, which in the psychologists' language produce a stimulus or induce reactive patterns, or drives. Seen in terms of man's larger development, they are condensations of emotional energy whose compulsive power can, however, be overcome and their captive energy released by calling them into consciousness and understanding their nature. Most psychotherapy has to do with unlocking these fixed "nucleations" of energy, which compare to free psychic energy as mass to kinetic energy.

The reader will note that my use of the word nucleation is intended to show the correspondence of stage six to stage two. These two stages, both at the second level, have to do with condensation of energy, and I am correlating the condensation of energy into nuclear particles with the condensation of psychic energy into archetypes.

Now, as Raymond Prince points out (in a passage immediately following his quote of Freud's comparison of the amoeba's pseudopods with human libido radiations), Freud used a term that makes the parallel to nuclear particles even closer than I have made it, although he had no such parallel in mind. Prince writes:

Within psychoanalysis there has been a good deal of discussion about the fundamental nature of the "psychic energy," the "protoplasm" employed in the various activities of the ego. . . . In speaking of this general area, Freud employs the German besetzung, meaning "to invest with a charge."*

*Prince, Raymond. "Interest Disorders." Journal for the Study of Consciousness, yoI.4,no.l (Spring 1971).

Thus Freud, endeavoring to describe energy, draws on the concept of charge, which is the third of three important linked concepts attached to stage two (motion, mass, and charge). The word besetzung, meaning to invest with charge, conveys just what differentiates the sixth stage, which we call volitional, from the compulsive second stage. The sixth uses charge, whereas the second is used by it since the electron is attached to the proton compulsively. Even with electricity there is the phenomenon of "induced charge," where the presence of a charge "induces" the opposite charge in a neutral body.

Freud supplies the point I missed in the example above about greyhounds chasing rabbits, a point which I should have noticed if I had made full use of the correlation with nuclear particles; for the "nucleation" of matter at stage two is always accompanied by "charge," that is to say, by the force of attraction or "attractiveness."

The difference between attraction and attractiveness is important because it serves to emphasize the element of participation that is excluded from the cosmology of science.

A response to science

In closing, we may note that the subject we have just covered - the demonstration of the existence of a plasmic directable energy - is especially difficult because such existence is nonobjective. Rather than defend it here (we have stated repeatedly the case for the nonobjective), we can note that "what's wrong" with science is not so much that it is materialistic and mechanistic, but that it tries to be entirely objective. As William James put it:

Compared with the world of living individualized feelings the world of generalized objects which the intellect contemplates is without solidity or life. As in stereoscopic or kinetoscopic pictures seen outside the instrument, the third dimension, the movement, the vital element are not there. We get a beautiful picture of an express train supposed to be moving but where in the picture, as I have heard a friend say, is the energy or the fifty miles an hour?*