*

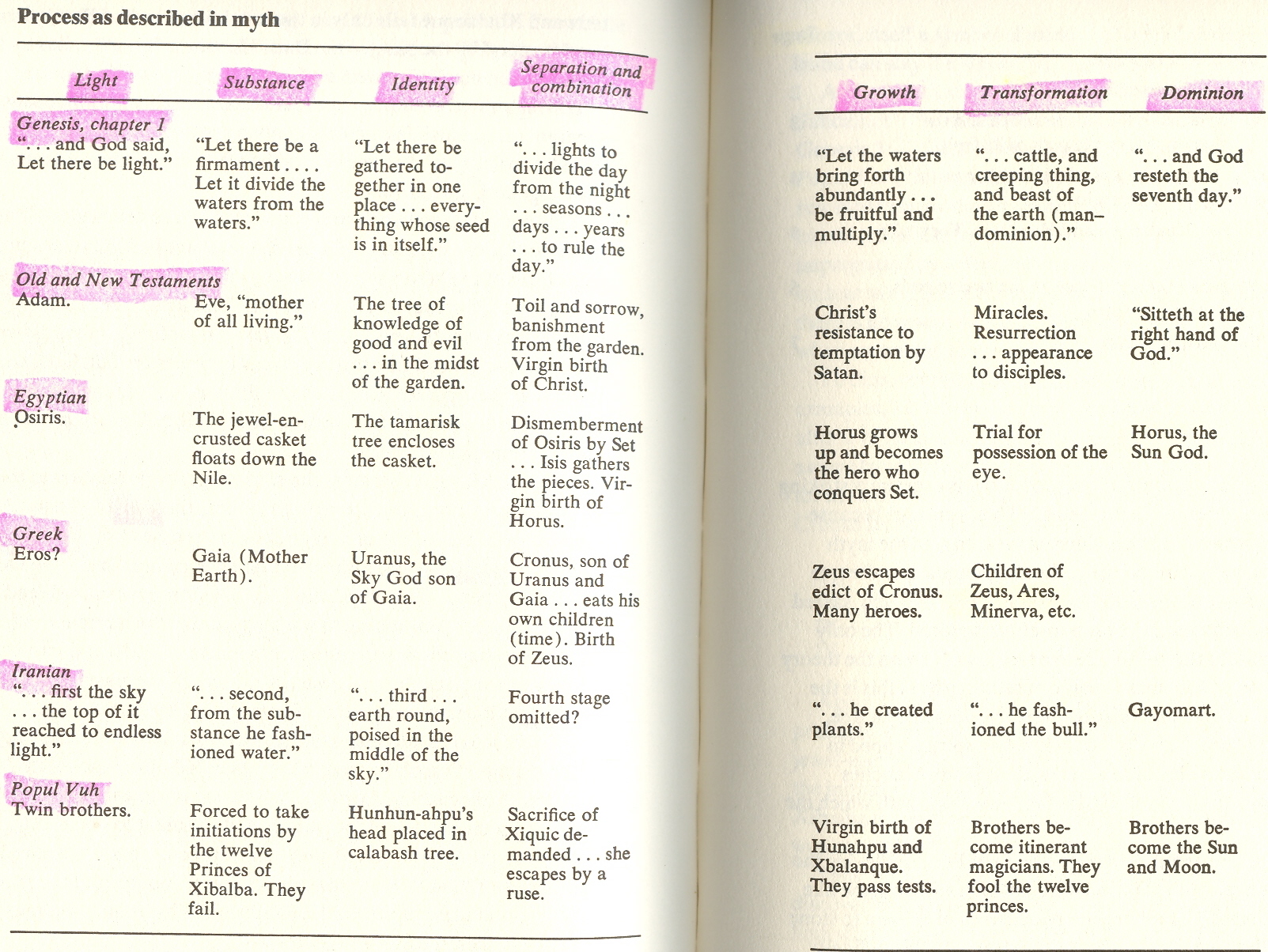

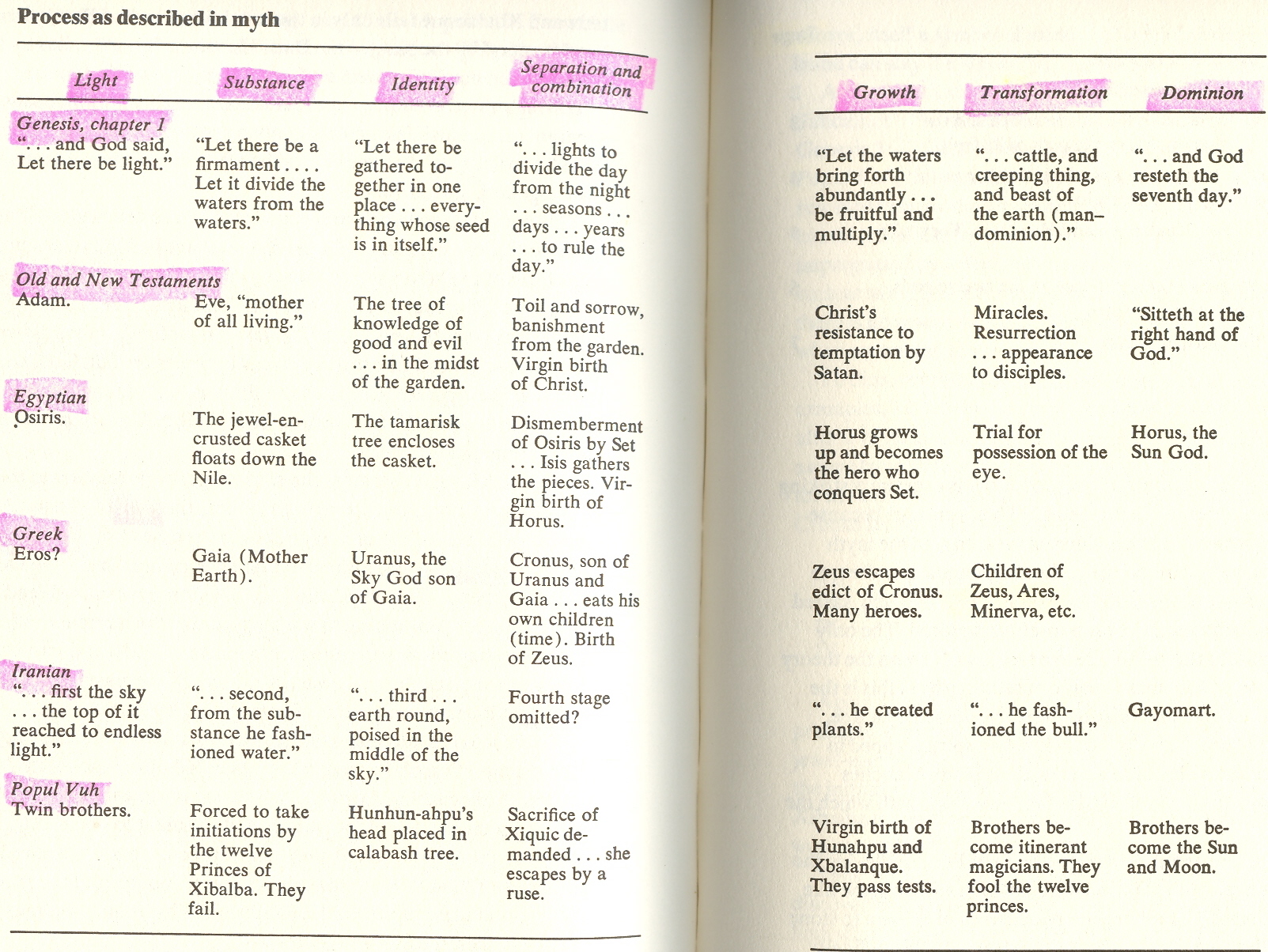

PROCESS

AS DESCRIBED IN MYTH

Arthur

M. Young

The

preceding chapters have been devoted to constructing a theory of

process. Drawing on science as much as possible for details, we have

sketched in its broad outlines a theory describing the interaction of

the creative with the inevitability of the laws of matter. This

interaction (or what the ancients called intercourse) produces a

progressive development manifesting in seven stages or kingdoms. We have

not attempted to find sanction for this overall thesis from science,

mainly because current science does not recognize the positive role of

uncertainty in cosmology. Science, in fact, has become so fragmented

into separate disciplines that it has lost sight of the unifying

principle that the word "universe" implies.

Such

a unifying principle was not lost on the ancients, for their

speculations were motivated by a powerful urge, if not to explain, at

least to describe the stages of creation and the fall of man. Their

accounts in myth and legend, seemingly naive, have an amazing sense of

wholeness, of integrity, and contribute in a way that science, with its

emphasis

on the explicable and on the detailed development of successful

techniques, has lost. Science, like a map, can furnish information, but

it cannot provide a compass. Myth supplies this compass. With its help

we can discover how to orient the map.

There

is no compulsion in this - everyone can still go where he pleases. We

should realize that the compass reading that orients the map does not

dictate or even concern one's own personal destination; it has only to

do with how to orient the map, which is essential for any use of

it.

Myth can help with the orientation we seek, for it is in rapport with

nature with which modern man has lost touch. This rapport with nature

- with

the unconscious; with the mysteries of life and death, of generation and

transformation; with that area of knowing which linked man with life

instead of holding him off, separately, as an observer permeates the

literature handed down to us in myth and legend, in art and symbol.

Approaching

myth

Many

important myths deal with the descent and ascent of man. If we include

cosmologies as a pertinent and necessary preface for the descent, and

hero myths as dealing with the ascent, unquestionably the more important

myths do fit the description. Indeed, if we get behind their superficial

expression, their content is surprisingly profound and rich in meaning.

Perhaps that is why they have survived. They echo in palatable form the

deeper truths of existence and have survived because of this alignment

with universal meaning. At this point a difficulty arises. Who is to

interpret this meaning? For myths, of course, must be interpreted - as,

indeed, they are, and in quite different ways.

Old

interpretations

Here

it is interesting to note the way in which Plutarch, as G. R. S. Mead*

pointed

out in 1906, considered the various theories of his day which professed

to explain the ancient myths and theologies. Among them was Euhemerus'

theory that the gods were nothing but ancient kings and worthies.

Plutarch dismisses this as an insufficiently satisfactory explanation.

The theory that gods referred to "daimons" (as exemplified in

Homer when the gods inspire men to act in certain ways, or otherwise

assist, punish, or reward them) he considers to be an improvement. He

also takes into account the theories of the physicists or natural

phenomenologists (who claim that Osiris represents the Nile, etc.) and

the "mathematicians" (who think of the gods as references to

the heavenly bodies, Osiris to the moon, etc.). From all of these,

Plutarch concludes

that no simple explanation by itself gives the right meaning.

*Mead, G. R. S. Thrice Great Hermes (vol. I, pp. 257, 318).

London: John M. Watkins, 1906.

"But,"

to quote Mead, "of all the attempted interpretations, he [plutarch]

finds the least satisfactory. . . those. . . content to limit

hermeneutics (explanation) of the mystery myths simply to the operations

of ploughing and sowing." With this "vegetation god"

theory Plutarch has little patience, and stigmatizes its professors as

that "dullcrowd."*

*Plutarch's criticism applies to many of the current theories stemming

from Frazer, who in The Golden Bough promotes the "vegetable

god" theory.

The

new: Freud and Jung

Now,

seventy years later, we have some new schools of interpretation, the

psychological, both the Freudian and the Jungian. Freud's attitude

amounts to a dismissal of myth from serious consideration. It reduces

all symbolism to the level of sex (instead of raising sex to a universal

principle of creativity). It is true that Freud made an important and

necessary contribution by exposing the hypocrisy of Victorian attitudes.

But in regard to a myth which openly states that the phallus of Osiris

is

its central theme, no such crusader is necessary. In fact, the myths

about Osiris - and, for that matter, the Greek myth of Uranus - are so

patently sexual that we may reasonably suspect the sex symbols conceal a

deeper meaning, and thus reverse the situation to which Freud's theory

of censorship applied.

Coming

to the Jungian interpretation, we draw closer to the true content of

myth. Jung, building on the rubble left by Freud, recognizes a deeper

layer, the collective unconscious, which is a repository not only for

the past or repressed memories of the individual, which lurk in Freud's

subconscious, but for the much more universal race memory. Here,

according to Jung, lie all the memories of mankind in a kind of

universal sleep, raising themselves from time to time in dreams or

flashes of surmise, possibly to warn us at some important crisis, but in

any case available as subliminal undertones that enrich us and provide

that curious resonance from the inner being that makes it possible to

"recognize" the true and the good, as well as to be

invigorated by old tales and legends. With regard to sex, the Jungian

theories again go a step

beyond Freud by elevating the feminine symbol to the status of the soul

rather than the immediate object of animal passion.

We

cannot, however, rest here. The Jungian concepts, though they go a long

and important way toward it, do not reach the true center of the myth. A

more extended study of the language of symbols reveals a much greater

variety of meaning than it is accorded by most Jungians. In the light

of the theory of process, the archetypes comprise a whole dimension

(level) of existence. They are the inhabitants of the psychic world and

the variety of their manifestations is almost unlimited. This variety

runs the gamut from universal archetypes to personal dream symbols,

cartoons - even ordinary language. They provide the substance of life.

The

translation of symbols tends to be limited by the range of understanding

of the translator. We, of course, run into the same limitation; but

progress is often like the group velocity of waves, in which the

individual waves arise at the rear of the group and push forward until,

just as they are merging at the front, they fade and disappear,

contributing to the general motion but vanishing as they get

"too far out."

The

grid theory and myth

Our

thesis at this point is the pertinence of myth to grid theory and of

grid

theory to myth. Readers still skeptical of the validity of grid theory

will naturally enter this new territory with a certain reserve,

withholding judgment until further proofs are furnished.

Unfortunately,

this reasonable reticence will not make any sense in the areas we have

entered, where proof is especially hard to come by. This chapter is not

intended as a proof of grid theory. Such proof as exists of grid theory

has already been given in earlier chapters. Since we are therefore

assuming that grid theory is more or less valid, the function of this

chapter is to draw on myth for guidance in the application of grid

theory to man, for orienting the map. We propose, therefore, to go ahead

and assume a correspondence between grid theory and myth. Our

justification is that we are thus able to draw from myth greater meaning

and pertinence.

There

is, however, besides the grid theory, a second hypothesis whose validity

must be assumed: that primitive myth was in rapport with the basic

workings of the cosmos and did correctly depict cosmological truths.

This hypothesis does not state why myth should be correct. It does not

tell us whether man invented fantasies which had validity because his

intuition perceived the truth, or whether there might not have been in

some remote age great leaders who taught theology and cosmology in a

form that could be grasped and retold by simple people.

For

example, even the quite remarkable instance of Swift's description of

the moons of Mars is susceptible to a double interpretation. Swift, in Gulliver's

Travels, explains that Mars has two moons, and gives their period of

revolution as very short - quite close to the actual periods of 7 hours 39

minutes, and 30 hours 18 minutes which is not what one would expect on

the basis of the fact that our own moon takes 27 days to revolve. Yet

Swift wrote his fable two hundred years before the moons of Mars were

actually discovered by Asaph Hall in 1877. Did Swift "intuit"

this remarkable bit of information, or did he learn it from some ancient

or forgotten source? Some maintain the latter, instancing the fact that

the Mars of mythology has his chariot drawn by two steeds, Phoebus and

Deimos (the names, incidentally, which astronomers later chose for the

red planet's two moons).

In

this connection, I will mention here that I have seen references to

the effect that the ancient Hindus held that neither Mercury nor Venus

rotates on its axis with respect to the sun. If this is true, it implies

a knowledge of astronomy surpassing that of the present time, for modern

astronomy, with the help of present-day instruments, has only recently

confirmed this lack of rotation for Mercury. Furthermore, temperature

measurements of the clouds of Venus disclose that its period of rotation

is very slow and thus confirm the Hindu teaching. Thus ours may not be

the first advanced civilization and, if this is so, myth may be the

remnant of ancient teachings rather than the result of intuitive wisdom.

Apologia

for symbols

As

we have said, myths demand interpretation, and our hypothesis is that,

since the universe is governed by and exhibits the attributes of

process, myth will recount this process in symbolic form. The question

might

still be raised: why symbolically? why not directly? This is an

interesting question. It thrusts back into the nature of language

itself, for what would a direct description of cosmology be? Recognize,

if you will, the great difficulty of the physicist in describing the

atom. First he had the picture of a billiard ball; then of a minute

solar system, with electrons like planets flying around a central sun;

then the Bohr atom, with orbits mysteriously regulated by quantum laws,

revealing that they must be in some special numerical relation to one

another; then the orbits giving way to a "probability fog."

The effort of the physicist to correctly interpret the atom, we noted in

Chapter VI, is like the effort of Scripture to describe the truth of

revealed religion: both have to draw on the sensible world for their

images.

This

is also true of a cosmogony, whether the beginning be described as the

creation of matter out of light, or as the intercourse of Sky and Earth,

or as the separation of the waters above from the waters below. The

images and words used are only a device to assist the mind. There are no

actual "things" at the level of electrons or in the first

steps of creation, and there is no image except one that will have to be

translated or erased. This is where the language of symbolism triumphs

in the end. It reminds one of that wonderful story, now decades old,

about Noel Coward sending a telegram and signing it

"Mussolini." When the telegraph operator saw the signature,

she cited a ruling that false signatures were not allowed. So Noel

Coward signed it "Noel Coward." The operator rebuked him

again. He replied, "But I am Noel Coward!" "Oh, in

that case," said the operator, "it will be all right for you

to sign it 'Mussolini.' "

Herein

is the defense of anthropomorphism. We translate the meanings we

discover in nature into more and more abstract entities and then, at

last, realize that however we translate them, we can understand only

that which is human, and we might just as well say the electron

"attracts" the proton. But let us examine symbolism further.

A

symbol is something that stands for something else and, according to the

modern view, the assignment is arbitrary. Thus, while in algebra the

letter x stands for the unknown, any other letter would serve as

well. In ancient times, to the contrary, there was an immediate and non

arbitrary connection between the symbol and its meaning, thus rendering

translation possible. Indeed, the language of symbolism, like

the language of dreams, can be translated precisely because the assignment

of symbols is not arbitrary, but guided by the inherent rapport between

the abstraction and the object symbolizing it.

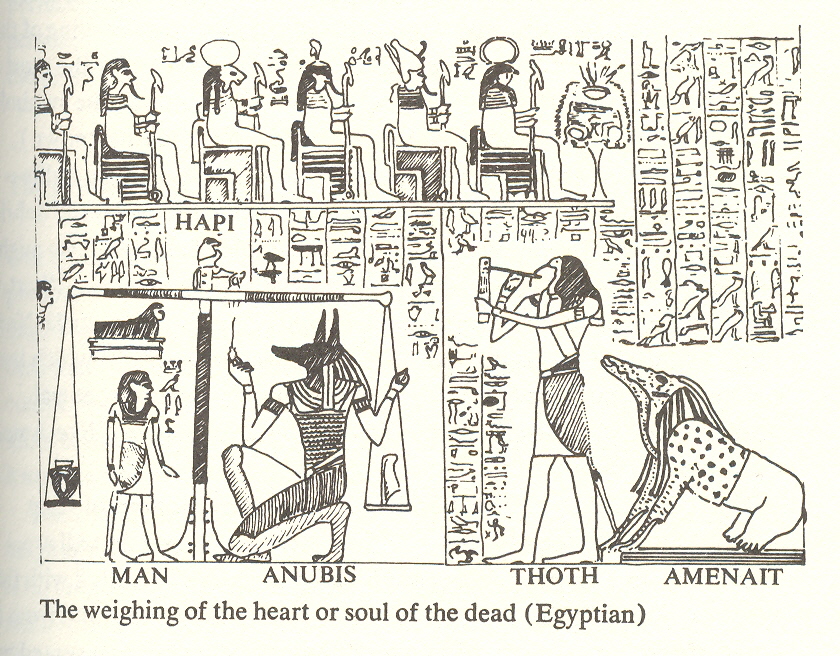

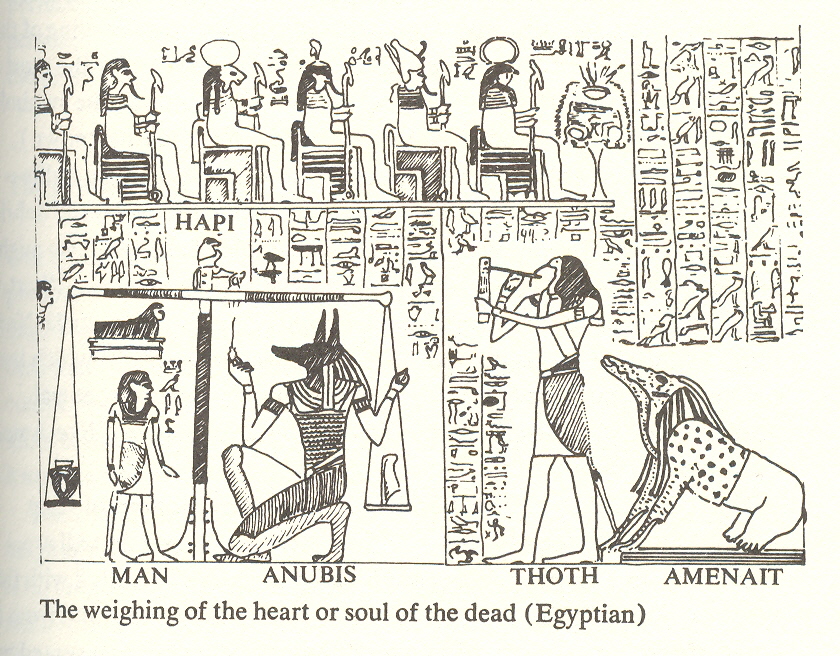

Let

us give as an example the painting representing the judgment after

death. It depicts the weighing of the heart or soul of the dead. In the

picture, the dog-headed god, Anubis, operates the scales; the mandrill

god, Hapi, makes the pointer reading; and Thoth, the ibis-headed god,

records the result. The "heart" is weighed against a white

feather, and Amenait, a hybrid monster with the head of a crocodile and

the rear of a hippopotamus, crouches nearby waiting to devour any

leftovers disqualified by the test. The message is quite clear even

without translation. But it is interesting to know some of the

particulars. Thoth, whose function is depicted not only by his holding a

pen and writing down the results, but by the ibis beak springing from

his head, symbolizes the power of the mind. Curiously enough, the name

Thoth is close to our word "thought," which describes his

role. But the Egyptians, having no abstract words like

"thought," gave Thoth an ibis head to symbolize his function.

Anubis, the dog-headed god, is man's faithful helper and guide.

With his exaggerated nose and ears, depicting heightened sensitiveness, Anubis represents the powers of discrimination. Hapi,

who watches the pointer, has the head of a mandrill. To anyone who has

observed a mandrill and noticed the extraordinary power in its

concentrated gaze, this way of emphasizing the accurate reading of the

pointer is brilliant.* The white feather symbolizes truth, for the most

interesting reasons. As we shall later see, air is, in general, the

symbol of

mind (as we use the term "to air" in the sense of making

known), and

as a feather moves air, so does truth move mind. The crocodileheaded

Amenait represents the physical world that recycles the debris.

*In some versions, the mandrill has degenerated into what seems more like

a decoration on top of the scales than an active member of the team.

Contrasting

with this very ancient "household of the self," we might

instance Walt Kelly's Pogo. Pogo's immediate circle includes Albert, an

alligator, Owl, and Churchy (from Cherchez la femme), a turtle.

Now Pogo, ostensibly a possum, is drawn with a round face from which

lines radiate, a symbol that everywhere represents the solar or central

principle, the spirit itself. Owl is clearly mind, and Albert, like

Amenait, the physical (body).

Comparing

Pogo and his friends with the four functions of Jung - intuition,

intellect, sensation, and emotion - we note that all are accounted for

except emotion, so Churchy must be correlated with this function. This

is borne out by Churchy's fondness for song and from his name, Cherchez

la femme. But why should emotion be represented by a

turtle? What is a turtle? A turtle is an animal with an armored shell

into which it withdraws under threat of danger. So the story depicts

modern man as wearing an emotional armor. Again, Pogo, or spirit, is

depicted as a possum since a possum is an animal that pretends to be

dead.

Now,

I'm sure Kelly had no such roles in mind when he created Pogo and his

friends. Indeed, if he had had such a notion consciously, it would

probably not have emerged with the telling conviction that the

unpremeditated version has. Whether in Kelly's cartoons or Egyptian

papyri, we have before us a language that is in rapport with the basic

truth of nature, not because it is highly conscious, but because it is

not. It is as unconscious as digestion or those other physical processes

that our

body is able to carry out with no assistance from the mind - such as the

healing of wounds, immunization against disease, growth of an embryo

and, for that matter, all growth. This instinctive functioning is

perfect and provides a sort of built-in compass that guides the

"natural" person, just as the sense of equilibrium,

established by a mechanism in the inner ear, enables us to walk upright.

The

grid and myth

Our

theme is that myth, in general, symbolically describes the arc of

process, which begins with the "descent into matter." In the

grid, process begins with undefined purpose or impulse, initially

completely free, and then takes on a series of limitations that

eventually tie it down to complete determinism. In myth, the

synthesizing or return half of the arc is sometimes a continuation of

one and the same saga; in other cases, it may be described in separate

myths.

The

real difficulty is in translation. Not only are myths in a special

language, i.e., the language of symbols, but in the final analysis, there

is

no language for the ultimate nature of things. The

physicist resorts to mathematical formulae, but never really knows what

he is talking about. He trains himself to avoid visualization, to

navigate through the darkness by the use of instruments. Only

occasionally does some flash of genius - like a stroke of lightning -

illumine the path for a moment and permit a new sighting to be

made on the goal.

Translation,

then, is our problem. Among other things, we must also translate what we

mean when we say the universe is process. Perhaps the most apt

expression of this thesis is the formula of quantum theory due to Dirac (a

and b are operations, h is Planck's constant, i is

imaginary) :

ab

- ba

= ih

This

is the celebrated equation which expresses the breakdown of the law of

commutation; that the operation a times b is the same as b

times a, or ab = ba. But even this has to be

translated; it is not enough to say that ab - ba doesn't

commute. We must so translate the formula that every element is

accounted for. Clearly, ab is one operation, and ba is its

inverse,

like going to town and returning. Going to town and returning gets us

back where we started, so the result is zero geographically. But when in

town, we signed a contract, we did something, and this was in

no

sense a geographical change of position. That it is not geographical is

signified by the letter i, which in the quantum formula

represents the square root of -1. It describes the action of h as

of a different nature from

the change of position described by ab and ba. The i is

imaginary, that is to say, in a different dimension, just as signing a

contract is different from moving from place to place, since one is a

value transaction, the other a physical transaction. So our reduced

formula, ab - ba = ih, says that process is an

involvement with matter (ab) and an evolvement from matter (-ba),

to produce a "nonmaterial" unit of action. The

matter, then, is means; the imaginary part, the end achieved, as in the

arc.

The

beginning of things

Judaic

It

is our thesis that myth, in its complete form, says the same. To begin

on familiar ground, let us start with Adam and Eve. Adam is the first

man, the first cause. By itself, first cause is as nothing; it

lacks something. So to it is added Eve, "the mother of all

living," the desire principle (Eve,

as desirable, epitomizes desire). Then comes the step that makes them

conscious of themselves and thus responsible for their acts - the eating

of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, the deed

that will make them wise as gods, and represents their involvement,

their contract with necessity, their enrollment in the school of life.

Next follows their expulsion from the garden, their descent into the world

where, the Lord says, "in sorrow shalt thou eat of it (the

tree) all the days of thy life." But we still do not have the whole

story. The emergence, or evolvement from matter, is not described in

Genesis. Perhaps it is best exemplified in the New Testament by Christ

himself, the hero who suffers crucifixion in matter and emerges

triumphant. And it is also exemplified by Christ in his teaching of rebirth.

Rebirth in Christ is, again, a symbol. It describes awakening, the

consciousness of the divine within

the self and of our ultimate potential, the capacity to be sons of God.

Egyptian

Such

interpretation brings another curious and important myth into place; the

Egyptian myth of Osiris, darling of the gods, against whom his brother

Set plots downfall. Set prepares a magnificent casket, encrusted with

gold and jewels, to the exact measure of Osiris. Then he invites all the

gods to a party, promising the casket to the one who fits it best. Each

of the gods tries it, and when Osiris gets in, Set slams down the lid

and throws the casket into the Nile. The waters of the river carry it as

far as Byblos, where it comes to rest by a tamarisk tree, which

eventually grows around the casket, enclosing it.

This

double emphasis on enclosure and restraint (first by the casket, then by

the tree) may be correlated with the progressive loss of freedom we have

come to expect at the second and third stages of process. The next

development, in which Osiris' sister, Isis, obtains possession of the

casket, only to have Set discover it and cut up Osiris' body into

fourteen pieces, which he scatters in the marshes, emphasizes that now

freedom is completely lost: Osiris is disintegrated and descends into disordered

fragments. This correlates with the fourth, or deterministic, stage

of process,

where the entity is fractured into parts lacking self-energy.*

*To define high and low in terms of unity versus fragmentation is

probably more basic and valid than in terms of literal height, because

order-disorder is a true "invariant" and not dependent on the

arbitrary direction of gravity.

The

next part of the myth begins the "return." Isis searches for

the fragments of Osiris and finds all but one, the organ of generation.

She nevertheless joins the fragments together, reanimates the corpse

and, by

union with it, conceives a son, Horus. Horus, represented with a falcon's

head, returns us to the "higher" or upper level, from which

Osiris descended. Horus is also the infant Sun God, reborn every morning

and, as a manifestation of Ra (the Sun God), returns the cycle to where

it commenced (since Osiris was the son of Ra).

The

reason for the overlapping manifestations of Horus lies in the fact

that he is both the beginning and the end of the cycle whose middle

is,

in effect, Osiris, God of the Lower World, the dismembered man-god.

What

is most interesting here is that the detail of the lost member of

Osiris,

and the conception of Horus, is another way of describing a virgin

birth. Neither Christ nor Horus has a physical father, a prior cause,

and the great lesson these myths teach is that the final essence, the

ultimate cause of life, is not a thing, but is cause itself. When we

come to the complete fragmentation and entombment in matter, to the

rock bottom, we cannot depend on any outside thing to lift us up. We must

do it ourselves and, in that act, we are reborn.

Greek

Our

next example is that most wonderful of myths, the Greek account of

the beginning of things. Actually, this is more a cosmogony than a myth

of man, but since both man and the universe are processes, the Greek

myth may be profitably examined in juxtaposition to the two we have just

considered. It tells that in the beginning, Gaia, or Mother Earth, was

made pregnant by Uranus, God of the Sky. So burdened was she with

frequent childbearing that she craved relief and, to this end, gave her

son, Cronus, a sharp sickle and persuaded him to use it. Cronus did so

and cut off the testicles of Uranus and threw them into the sea. From

the blood came the Furies, and from the sea foam was born Aphrodite, or

Venus. Cronus became king but, having been told he would in turn be

overthrown by a son, he ate his own children as fast as they were born.

His wife, Rhea, by the stratagem of wrapping a stone in swaddling

clothes and presenting it to Cronus, succeeded in saving her son, Zeus,

who overthrew and succeeded his father as predicted.

In

Cronus, we have the principle of determinism, which cuts off and regulates

not only his father, but his own children. We would, therefore,

relate Cronus to the fourth principle, and Zeus to the fifth, since he

escapes from the regulation of Cronus as vegetation "escapes"

from determinism through its progeny. Note the emphasis on stratagem as

the way to get around the "law" of Cronus.

"Stratagem" is another way of viewing this "escape"

to regained freedom. The "Wily Ulysses" is the Greek

representation of the hero who escapes the restraint of determinism.

This may seem a far cry from the Christian virtues until we

recall that Christ as a child was spirited out of Bethlehem to escape

the decree of Herod.

The

seven stages

Greek

The

Uranus-Cronus-Zeus myth, which is an account of the generation of the

universe, lends itself to interpretation in terms of the actual stages

of process. The myth depicts a succession: Cronus is the son of Uranus,

and Zeus is the son of Cronus. Investigating further, we find that

Uranus is the son of Gaia (Earth). Note the sequence:

|

|

|

|

|

Stage |

|

Gaia |

Mother

Principle

|

= |

Substance

|

2 |

|

Uranus |

Son

of Gaia

|

= |

Seed Principle (identity) |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cronus |

Son

of Uranus

|

= |

Determinism |

4 |

|

Zeus |

Son

of Cronus

|

= |

Escape

from determinism |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gaia,

or Mother Earth, conforms to substance. She supplies the substance, and

correlates to Eve, "the mother of all living," in the Adam

and Eve story (Genesis 3:20).

Uranus'

seed impregnates Mother Earth. This seed principle correlates with

identity, stage three.

Cronus

eats his own children, and thus he represents limitation by law, or

determinism. In emasculating his father, Cronus had similarly

delimited his father. Cronus is time* (chronometer, chronic,

chronology), or, again, Father Time with his scythe.

*Francis Bacon gives this interpretation in Wisdom of the Ancients.

Zeus'

escape from being eaten by Cronus, from limitation by time, correlates

with the fifth stage of process, the power of vegetation to project

itself through its seed, and thus conquer time. Zeus is also known for

his progeny.

Zeus,

however, is but one of many heroes in Greek mythology. Hercules, Jason,

Theseus, Perseus. Each one is significant in the context of the arc.

The

Greek myth of creation gives us no clear correlation to the first

stage,

though we can definitely say that there was something before Gaia. Some

accounts give Chaos as the origin of all. To quote Kerenyi:

Ancient

night conceived of the Wind and laid her silver egg in the gigantic

lap of Darkness. From the Egg sprang the sun of rushing wind, a god

with golden wings. He is called Eros, the God of Love. But this is

only one name, the lowliest of all the names this god bore.*

*Kerenyi, Carl. The Gods of the Greeks. Translated by Christopher

Holme. London: Thames & Hudson, 1951; New York: Grove Press, 1960,

and Greenwood Press, 1962.

It

would be consistent with other accounts if we could claim that Eros set

the whole thing in motion and was the father of Gaia, but we cannot.

Hesiod places Chaos first, with Eros born after Gaia, as a brother or

co-equal with Gaia. Perhaps the Greeks, as the first materialists, just

did not give to light and fire that primal function that is their right.

Judaic

To

obtain a correlation with the first stage, we may turn to the account in

Genesis:

1:1 In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

1:2

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the

face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the

waters.

1:3

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light . . . . the first

day.

Iranian

The

Iranian legend of the beginning of the world is as follows:

In

former times the two realms of Light and Darkness. . . constituted

a

complete and balanced Duality. This equilibrium was disturbed when the

Prince of Darkness was attracted by the splendor of the realm of Light.

Before the threat of his onrush the Father of Greatness evoked a number

of hypostatic powers of light. Their defeat and subsequent disappearance

into darkness lies at the origin of the state of mixture.*

*Dresden, N.J. "Mythologies of Ancient Iran." In Mythologies

of the Ancient World. Edited by Samuel Noah Kramer. Garden City,

N.Y.: Doubleday, 1961.

The

word "hypostatic" means "having substance," so the

ancient myth seems to be describing an aspect of light which has only

recently come to be recognized, i.e., that light exists in the form of

finite bundles or photons, each having a particular energy.

Dresden

goes on to say that "among the first hypostases which were absorbed

by darkness was primeval man or Ohrmizd, as he is known in Iranian

sources."

The

complete Iranian account as Dresden gives it* can be correlated to the

grid stages as follows:

*Ibid., pp.

338-339.

Stage

First,

he created the sky, bright and manifest. . . in

1

the form of an egg of

shining metal. . . . The top of it

(Light)

reached to the Endless Light; and all

creation was

created within the sky. [The expression "reached to

endless light" seems to anticipate modern ideas of the

electromagnetic spectrum.]

Second,

from the substance of the sky he created

2

water. . . . [We have

frequently mentioned the

(Substance)

resemblance of nuclear particles to water and

substance.]

Third,

from the water he created earth, round, poised

3

in the middle of the

sky.

(Having a center)

(Number

omitted) And he created minerals within the earth. . . .

Fourth,

he created plants. . . .

4

Fifth,

he fashioned the . . . bull. . . .

5

Sixth,

he fashioned Gayomart (the first man). . . .

6

(The seventh was Ohrmizd

himself.)

7

In

this Iranian account, plants actually are numbered as coming fourth and

animals fifth, instead of at the fifth and sixth stages. Minerals fall

in the fourth stage, but are not numbered. It would be my opinion

that

the writer confused two of the earlier stages and combined them because,

although the names are different, the descriptions resemble the

corresponding stages of the grid. The third stage, although called "earth,"

is described in a third-stage way ("round, poised in the middle of

the sky. . ."), which sounds like the third stage of the

grid-"having its own center." Since the next numbered stage is

the creation of plants, the stage that is missing is that of minerals,

which we include in the molecular

kingdom.

Mayan

Less

widely known, but one of the most interesting, is the myth in Popul

Vuh, the

16th-century manuscript, written in the Quiche Indian language, which records

fragments of the mythology of the Mayans.* As the Popul Vuh recounts

it, the story begins with the twin brothers, Hunhun-ahpu and Vukub-Hunhun-ahpu

playing ball in Heaven. The twelve Princes of Xibalba (gods) send their four owl

messengers to Hunhun-ahpu and Vukub-Hunhun-ahpu, ordering them to appear for

their initiations. Failing these, the two brothers pay with their lives, and the

head of Hunhun-ahpu is placed in the branches of the sacred calabash tree, which

becomes laden with luscious fruit. Xiquic, the virgin daughter of Prince

Cuchumaquic, learns of the sacred tree and, desiring some of its fruit, journeys

to it. When Xiquic puts forth her hand to pluck the fruit, some saliva from the

mouth of Hunhun-ahpu falls into her palm and the head speaks to her, saying,

"This is my posterity. Now I will die."

The

young girl returns home. She becomes pregnant and is questioned by her father,

who refuses to believe her story. At the instigation of Xibalba (the gods), the

father demands her heart in an urn. Xiquic persuades her executioners to spare

her life. In the urn, instead of her heart, they place the fruit of a certain

tree whose sap is red and has the consistency of blood.** In due time,

she gives birth to twin sons, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, who grow up and do great

deeds. The Princes of Xibalba hear of them and summon them to the mystery

initiations, which take seven days and are intended to destroy them. These are

the same initiations at which their father failed, but Hunahpu passes all the

tests

and Xbalanque fails only in the last, in the Cave of Bats, where his

head is cut off by the King of the Bats. Hunahpu, however, has by this

time attained magical powers and restores his brother to life.

*Popul

Vuh. Translated by

Delia Goetz and S. G. Morley. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950;

London: Wm. Hodge & Co., 1952.

**Note

here too the ruse to escape the law of the fourth stage.

Having

passed their initiations, Hunahpu and his brother become itinerant

magicians! They go about giving performances in which they do

extraordinary tricks: one carves the other into pieces and puts him back

together, and so on.

This

is most interesting, for it supplies what is often neglected in other

myths, the sixth stage. Of the fifth we have had many examples: it is

the birth of the hero and his "passing of tests" (as with

Hunahpu and Xbalanque), the twelve labors (as with Hercules), the

slaying of dragons (as with Perseus), etc. The seventh, or final, stage

is where the hero reaches god-like status (Horus becomes the Sun God,

Christ "sitteth at the right hand of God the Father," and

Hunahpu and Xbalanque become the Sun and the Moon). But the sixth is

not often clearly enunciated.

Let

us recall what character the sixth stage, by its relation to the second,

must have. The second is attraction, the spell of illusion.* So

we could expect the sixth to be similar; but in the case of the Popul

Vuh, the self projects illusion, rather than being entrapped

by it. We have referred earlier to "transformation" as the

more generalized reading for the mobility appropriate to this stage and

in the reference in fairy tales to the magicians who change into mustard

seeds, and into hens who eat them, etc. In any case, in this myth we

have magic or the creation of illusion, the inverse of entrapment

by illusion.

*Mircea Eliade, in Images and Symbols (translated by Phillip

Mairet, New York: Sheed & Ward, 1969), gives a full chapter to

"The God Who Binds." Binding for Eliade is by magic spells,

but we generalize the concept to include the loss of freedom due to

"attraction by substance," that is, the second stage.

To

return to Hunahpu and his brother, their performances of magic reach the

attention of the twelve Princes of Xibalba, who invite them to perform.

After causing the palace of the princes to vanish and reappear, they

cut up the pet dog of the princes and restore it to life again.

Intrigued, the princes ask if they could be cut up and restored. The

brothers assent, and cut up the princes, but do not restore them!

This

concludes the drama. Hunahpu and Xbalanque become the celestial bodies,

the Sun and Moon.

The

twin brothers play ball in

Heaven.

1

They

fail their initiations (deceived by illusion*).

2

Hunhun-ahpu's

head is placed in the calabash tree and the

Lords

of Xibalba say, "Let none come to pick of its

fruit."

3

The

maiden, Xiquic, comes to pluck the fruit and becomes

pregnant.

By a ruse she escapes

execution.

4

Twin

sons are born to her, Xbalanque and Hunahpu. They

take 5

the

initiations and succeed.

The

twins perform magical tricks and decieve the twelve

gods, 6

cutting

them up and not restoring them.

The

twins become the Sun and Moon.

7

*In the first test the brothers are deceived by a wooden figure in the

likeness of one of the gods. Note that in stage six, this is reversed;

the twins deceive the twelve gods.

Summary

Comparing

these several accounts, the resemblance is especially striking in the

recurrence of the tree at the third stage. This is curious because the

tree in each case seems to have a different meaning. In the myth

of

Osiris, the tree grows up around the coffin. In Genesis, it is the tree

of the knowledge of good and evil. In Popul Vuh, it is the sacred

calabash tree in which the head of Hunhun-ahpu is placed. The only

explanation I can find for this reference to a tree is to draw on the

theory that at this stage, process becomes capable of relationship (this

is the form, or conceptual, stage), and relationship is expressed by a

tree, as

in the term "family tree." This is the third stage, spirit

trapped in mind, represented by a tree because a tree with its many

branches (ramifications)

suggests the many kinds of relationships with which the mind deals.

The

"trap of mind" is exemplified by the myth of Perseus slaying

the Medusa. Medusa is depicted with a head from which snakes grow like

hair (the powers of mind). Her effect on people is to turn them to stone

(the mind "objectifies," i.e., makes inert). To deal with this

difficulty and avoid being himself turned to stone, Perseus looks at her

in a mirror,

itself a symbol of mind ("Mind is the slayer of the real; only the

mind can slay the slayer," as the teachings of Zen put it).

At

the fourth stage (complete loss of freedom) there is emphasis on

difficulties ("in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy

life," Genesis 3:17; in the Greek myth, Cronus eats his own

children; in Popul Vuh, the princess Xiquic must be sacrificed).

The problem is resolved only by the virgin birth of the hero. In the

Osiris myth, Isis conceives Horus from the corpse of Osiris; in Popul

Vuh, Xiquic is impregnated by a dead head. But this similarity is

not imitative, is not such as to suggest a transmission from Egypt to

America. Superficially, there is no resemblance between the myths. It is

only at the deeper level, when correlated to process, that the

similarity emerges.

To

discover this basic correspondence, let us note that all these examples,

including the cosmogonies, deal with a descent, followed, after a

virgin birth or a ruse, by an ascent or, in the case of Cronus,

an escape from limitation (determinism). Thus the birth of Zeus,

famous for his amours and his progeny, restores the power of generation

that Cronus terminated in Uranus.

I

1 Freedom (potential)

7 Freedom (actual)

II

2 Binding

6 Unbinding = Motion

III

3 Form

5 Growth = Zeus

IV

4 Determinism

Again

in the Osiris myth, Horus at stage four conquers Set, the principle that

first trapped Osiris and imprisoned him in the jewel-encrusted casket at

stage two. In Popul Vuh, the twin sons pass the initiations their

father failed. As magicians, they cause the Lords of Xibalba to become

victims of the same weapon (illusion, stage six) that was used against

their father at stage two.

Thus

we can place the seven stages of myth on four levels and discover that

at each level the right-hand side frees itself from the limitation that

arose on the left at this level. The levels for myth too have the

meaning we found for the kingdoms: level I is freedom, level II is

binding, level III is form, and level IV is determinism.

The

Reflexive Universe

Mindfire