*

RHYTHM AND REALITY

When Alponse Karr, in 1848, evolved his happy phrase, "the more it changes, the more it's the same thing," he gave an impudent and Gallic lightness to one of the most fundamental of human insights, to wit, that there is a factor of certainty on which man may depend, throughout life's shifting confusions. Francis Bacon, by comparison, is ponderously scientific. "It is sufficiently clear," he explains in his De Natura Rerum, "that all things are changed, and nothing really perishes, and that the sum of matter remains absolutely the same."

Closer to the astrologer's heart is the creative imagination of the early Hebrew mind. It is a singer of Israel who really gets the concept of stability into words of power. The Psalmist shows the way for every individual who would get a steadying hand upon the course of his own destiny.

The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork. Day unto day uttereth speech, and night unto night sheweth knowledge. There is no speech nor language, where their voice is not heard. Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. In them hath he set a tabernacle for the sun, Which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber, and rejoiceth as a strong man to run a race. His going forth is from the end of the heaven, and his circuit unto the ends of it: and there is nothing hid from the heat thereof.

(Psalms, 19:1-6)

The hazards of life have always been a persisting nightmare in human consciousness, despite the dulled sensibility of the masses, or the thin coating of a rational self-aplomb by which most cultured individuals seek to insulate themselves from their primitive apprehensions. The mortality of the young among both men and beasts in ancient times, together with the common handicaps and incapacities resulting from accident or disease, and the loss of opportunity or advantage from simple inability to muster an adequate energy or cleverness, all dramatized the insecurity of existence. Personal relationships of blood and marriage were no more dependable than others. Every community faced the chance of on-sweeping war, famine, pestilence, flood and earthquake, often without warning, and there might be nothing at hand of a physical sort to which a frightened soul could cling. Man's fears have long remained the principal ingredient of both his conscious and subconscious self-awareness.

There were unchanging elements in the midst of all these things, however, even if they were no more than the certainty of repetition in calamity's onset. While men were utterly helpless against the risks of existence, they were yet, curiously enough, able to reproduce or repeat their own identity in their children. Moreover, they saw the foliage and creatures around them survive in this species of metempsychosis — which seems to have been a simpler idea for the savage than for his learned descendants. It was obvious to primordial man that life, while characterized by the utmost instability on the surface of existence, nonetheless presented a pattern of continuity. Imperfectly as he may have sensed the fact, it identified a greater reality in his thinking. The human mind felt itself a part of this continuity, especially in the realization whereby the human individual became religious, or began to know God. Here was a divine instinct which established hope and faith as the counteragents for every stark deficiency in self-integration.

The job of identifying the process whereby man gets the inner or subjective side of himself out into the unstable world of phenomena about him, making his understanding objective enough so that he can point to it, and thereupon refine it as knowledge and philosophy, belongs to the anthropologist and the psychological theorist. The astrologer merely observes that the basis for any such transition — in which an elementary creature becomes a social animal — is the discovery of some reference of stability in the everyday world to which a self-assurance can be assimilated. Such a frame of orientation, unless made a matter of imagination, must be found in nature. Out of all possible forms of natural religion in this sense, the worship of the sky — that is, man's ultimate anchorage of his consciousness in the completely dependable vault of heaven — is the most significant in religious history. It is the historical beginning of horoscopy.

The survivals of a primitive animism in astrological practice show how man's self-assimilation to nature can take place on the superstitious side, that is, in an enthronement of the fearful rather than the hopeful and self-reliant aspects of consciousness. There are still those today who go no further than the imitative magic of the savage, seeking to propitiate evil by a species of mental reproduction. They worship it by the abject respect they show it, and by the degree to which they regard it as inevitable. Devotees of astrology on this level always surrender to unfavorable indications. They invite calamity by making no effort at all to utilize the conditions constructively. They expect good things to come to them because Venus smiles or Jupiter chuckles in his beard, so to speak, quite irrespective of anything they may do to co-operate with the happier potentiality. They are the people who carry an ephemeris of the planets' places in their pocket, to make sure they overlook no chance to subject the most trivial details of their living to the guidance of an aspectarian. They make a virtue of their complete inability to act with wisdom or intelligence apart from a conformity to the limitation they accept in every passing moment, and so they regress unsuspectingly to the utterly hazardous world of the savage.

Primordial man himself, in contrast with this degeneracy of modern self-reliance, has left ample testimony to his very clear realization of a steadiness in nature. He often saw, in the cosmos, an order on which anyone could depend in a more mature way, thereby bringing peace and happiness into his own private affairs. He developed the credo to which the Psalmist has given voice. The heavens with their regularity of rise and set, the unimpeachable rhythm of day and night, the unswerving path of the sun and stars — these are reliable things in a context of even the greatest confusion. The heat of the sun becomes a recompense for man after the storm and cold, and there remains no corner of experience where the sustaining power of an ultimate reality cannot be found. The reassurance written in the eternal sky is that the unlimited ongoing can become very personal. This intuition of unquenchable energy, of an inexhaustible creative vitality, is brought out most characteristically by the Old Testament's colorful figure of the bridegroom. The youth, taking on his full adult responsibilities as he has a proved knowledge of his own strength, represents the true cosmic stature of all men and women.

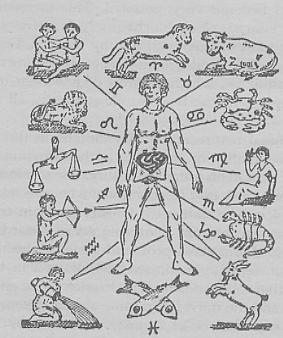

The continual recurrence of phenomena in the heavens, the rhythmic reality of the ages is the firmament, are a prophecy of man in his immortal reality. The subtle assurance here transforms risk into freedom, while chance takes a new form as choice. The individual is established in the sky to symbolize his capacity for mastering every hazard of lesser being, and to dramatize a profound psychological principle which the ancients approximated rather well in their mythology, or their allegorical half-realizations. The analogy between man and the universe became almost a commonplace of thinking with the rise of a conscious philosophy. The doctrine of MICROCOSM and MACROCOSM — popularizing the idea that the individual is the cosmos in miniature, while the greater universe is the total man in his real being — has been traced from the earliest Greeks, as Heraclitus and Empedocles, through Plato and Aristotle, on down into the modern period. The major work of Rudolf Hermann Lotze is entitled Mikrokosmos, and the concept has been carried to an interesting extremism in the monads of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz.

Astrology, rather than conventional science or philosophy — or even the occultism which leans most heavily on this correspondence — has put the conception of the heavenly man to work in a practical or everyday fashion. The SIGNS OF THE ZODIAC, as allocated to various parts of the body, beginning with Aries at the head and ending with Pisces as ruler of the feet, enable the astrologer to visualize an actual human organism — in a complete generalization of its powers, of course — stretched around the whole empyrean vault. This zodiacal creature, taken down from the sky, has graced drug-store almanacs and the more blatant sort of astrological publications for generations.

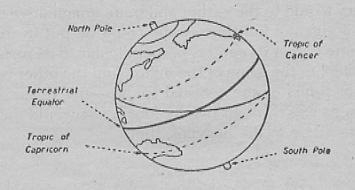

The significance of the heavens in astrology arises from their charting of entirely human relationships, represented by this popular form of anatomical macrocosmos. The celestial indications are developed from two different points of view, however, and the horoscope is created by blending them. First in ordinary public interest is the zodiac. It provides the more general perspective, and delineates the dependable or ordered factors as in contrast with the more individual elements of hazard, risk, chance, choice and free will. The zodiacal circle is the path of the sun, as measured or seen from the surface of the earth, and it is, actually or astronomically, the orbit of that latter body. The annual movement of the sun swings to the north from December to June, and to the south in the other six months, reaching the Tropic of Cancer above the equator and the Tropic of Capricorn below. The school-master's globe usually shows the course of this journey in the following fashion:

The concern of these opening chapters is the celestial EQUATOR rather than the zodiacal circle (or ECLIPTIC, in more technical designation). The signs of the zodiac, representing the relatively eternal or unchanging features in man's character — as these in their turn are revealed or mirrored in the firmament — are the consideration of Part Two in this text, when the analysis turns to the constants in experience. It must be realized, however, that both these great circles used in astrology — that is, the ecliptic or sun's apparent path, and the terrestrial equator as it is extended out into the celestial sphere — are created by the motions of the earth, and so are phases of the globe's activity in a complex of physical energies. The heavens dramatize the basic relations in man's life, but they are only able to do so because the planet on which he lives is an active participant in the ceaseless and restless balancing of mass against mass in the larger milieu of a solar system. The movements of the earth are the basis of astrology, completely and in every respect, even in connection with the other moving bodies, as will be explained in Part Three.

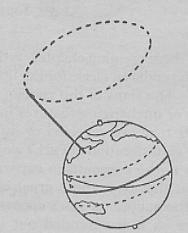

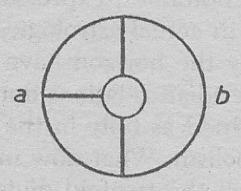

It has been seen that when the individual has an actual beginning, he is really describing a horizon in the physical cosmos. This represents him as an entity, mathematically, in the special way already indicated. He becomes measurable, astrologically, because he thereby delineates his own personal universe. Thus the baby has been pictured, in a purely symbolical sense, standing outdoors and turning around with out-stretched arms to complete the basic dichotomy. Now, in order to get any notion of the horoscopic mechanism, it is necessary to add to the earlier and quite imaginative description. If a gigantic knitting needle could be put in the earth — with one end at its center, perpendicular to its surface and also parallel to the spine of the infant, and the other reaching the outer limits of the celestial sphere — the turning of the globe on its axis through twenty-four hours would describe a complete circle in the heavens, thus:

If the birth took place at the equator, shown here by the double line, the needle would simple retrace the extended or celestial equator in which the diurnal or daily motion of the earth is measured. However, both such circles of axial motion are parallel, and in consequence it is quite proper to consider the activity of the one as taking place in the other, mathematically. They show the same movement in the same fashion, which makes them functionally identical. The astrologer, therefore, always employs the latter, where he establishes the houses of the horoscope as shown in Chapter One. The circle which there defines the universe or heavenly vault is now seen to be the celestial equator (representing all circles parallel to it).

The Measure of Reality by Motion

It is necessary to digress at this point, to emphasize the fact that all astrological symbolism is created by the actual movement, in one phase or another, of whatever may be symbolized. Nothing in equilibrium is ever significant in its motionlessness. In fact, there is no absolute or static reality in any possible substance or relationship, as modern science has begun to make very clear.(1) Objective existence is merely a condition of constancy in a co-operative activity, whether in a simple aggregation of atoms or a complicated social structure. Man himself at all points, physically and psychologically, is a complex of motions. His organism has its continuity in a dynamic economy of chemical changes, supporting the distribution of the energy which facilitates them. Any living animal takes in oxygen and gives off carbon dioxide, consumes proteins and releases nitrogenous waste, and so on. It exists through its unceasing interaction with its total environment. The symbols of astrology, to have any functional effectiveness in the mind, must diagram experience in the terms of the movements which constitute both man and his world, and which thereby permit the latter to take on the representation of the former.

(1) The Bohr and Heisenberg concept of uncertainty is an interesting exposition along these lines at the time this text is prepared for publication.The horoscope and its suggestive indications are all derived from the motions of the earth originally, since every other heavenly activity is mediated through the celestial body on which man finds himself. His presence on the globe means that, in his experience, it remains motionless as the ground of is being, and that its movements are necessarily translated elsewhere. Thus its most important daily rotation on its axis causes the entire heavens to turn around, in a very true sense. This establishes the celestial equator, or the circle of the houses, as the foundation for horoscopic delineation. These equatorial divisions present the particular orientation of the individual in the world he has made for himself, and they are the primary mansions of astrology. They, like the earth, remain stationary in man's experience. They are the basis of his private reality, and the entire celestial vault turns through them clockwise — as viewed in the normal diagram — rising in the east and setting in the west every twenty-four hours.

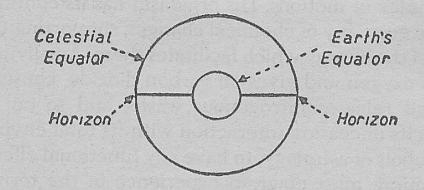

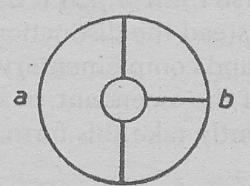

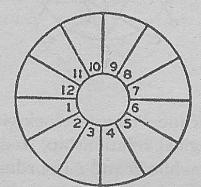

There are twelve houses in the celestial equator, as already indicated in preliminary fashion, and it has been explained that they are established first of all by the individual's original horizon. This basis for the horoscopic figures has been shown on page 7 (first chapter), as follows:

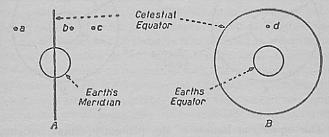

The horizontal line is the horizon seen sidewise, as pointed out before, and it must be remembered that the two hemispheres together comprise the entire cosmos. In other words the houses are not just geometrical pie-shaped divisions of the equatorial circle but are rather sections of the whole heavens, like the segments of an orange when it is peeled. Hence a planet, to be in a given house of the horoscope, does not have to lie in the plane of the equator, but may lean away on either side to a considerable extent. This may be seen by comparing the diagrams on the next page, figure A turning the horoscope to give a sidewise view, and figure B showing the same planetary situation in the normal fashion of representation. Positions a, b and c in the first instance are all identical with d in the second.

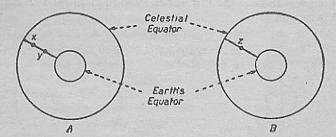

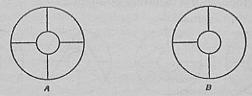

The lean of a planet — that is, more technically, its latitudinal co-ordinate in relation to either the equator or zodiac — has astrological import in certain refinements of technique, but these are beyond the scope of the present text. Therefore its DECLINATION and LATITUDE, or the amount of this lean away from the plane of the equatorial houses and of the zodiacal signs, respectively, are not discussed here. They are always given in an astrologer's ephemeris, but in fundamental horoscopy no attention is paid to anything but the location of the various bodies relative to each other in terms of their situation around the circle of the houses and signs, or their RIGHT ASCENSION and celestial LONGITUDE, respectively. The latter takes care of all the functions of the former in normal practice, so that right ascension may be ignored, as well as declination and latitude, in simple work. The position of a planet in amount of distance away from the earth — the radius vector of the astronomers — is of no astrological significance whatsoever, since all horoscopic delineation stems entirely from celestial movement as interpreted through angles of arc in geometrical relationship. Hence, in the following comparative figures, with A showing distances from the earth and B the astrological convention, the positions x and y in the former case are identical with z in the latter.

The equatorial houses of the planetary CHART, FIGURE, MAP, WHEEL, NATIVITY or HOROSCOPE of whatever heavenly elements are enlightening to the astrologer. The zodiacal signs are an additional and supplementary means for doing precisely the same thing, giving an added dimension of insight to astrological judgment. Understanding begins with the houses, then passes on to the signs in due course.

With this much made clear, in preliminary form, the next task is to gain some initial understanding of the factors by which the horoscopic wheel becomes a twelvefold screen of indicators. Leaving the zodiac for later analysis, what is the basis for the equatorial mansions? This first circle presents the rhythm of reality in the more intimate outreach of human consciousness to cosmic certainties, leaning upon the "day unto day" which "uttereth speech," and the "night unto night" which "sheweth knowledge." Its houses chart the commonplace situation of normal experience, and the question of present importance is, how do they do so?

The answer has been given in considerable part, as far as any foundation realization is concerned, through an exposition of the dichotomizing technique, and its demonstration of the necessity that the mind encompass its momentary world — that is, the totality of elements in any context of being — by a progressive sorting out of pertinent relations. The horizon is the beginning in any process of self-realization. It is the actual basis of the individual horoscope, and also of all astrological meanings.

A second great dichotomy arises from practically the same factors that define the horizon. As man stands on the earth's surface, creating the ground of his being, he also divides all the potentials of life, quite literally, into two great hemi-spheres of (1) the things he faces, or to which he gives conscious attention, and (2) those he puts behind him, or on which he depends more or less subconsciously. What is above or below the earth — to use the astrological terminology in respect to the first great horizontal division — is what life provides by way of a more objective context, on the one hand, as against what constitutes the reservoir of the race, on the other. The distinction between what an individual confronts, and that on which he he turns his back, is a dichotomy of experience on the basis of a real human choice or discrimination, not of a mere immediate situation. Man is symbolized in himself as he faces east — where the heavens rise, and where he reaches out to that which is novel — but is represented by what is essentially other than himself in anything which lies behind him, and which is setting as far as he is concerned, i.e., that which is passing into a consequent or a secondary significance. Hence the new dichotomy creates a sort of up-and-down horizon.

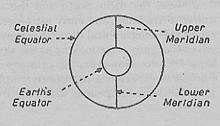

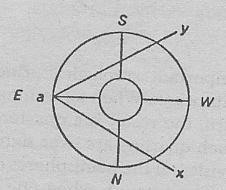

Astrology terms the upper point the MIDHEAVEN, or uses the abbreviation M.C. for the Latin medium coeli, while the other end of this meridian axis is identified as the NADIR, the I.C. or imum coeli.

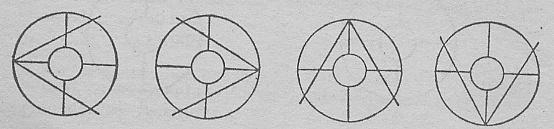

These two fundamental divisions at the horizon and meridian, in man's total world of experience, complete the physical or astronomical foundation for the symbolism in astrology. They establish the basic axes of the houses. Because they are the most important part of the conventional horoscopic map, they are often emphasized by specially heavy lines in printed horoscope blanks, thus:

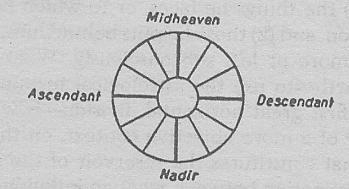

The ASCENDANT and DESCENDANT are the horizon points corresponding to the nadir and midheaven. (The nadir has a logical priority to the midheaven, as will be seen in the next chapter, but it is seldom given first consideration.) These four interceptions of the equatorial circle by the two basic axes are known to astrologers as the ANGLES of the chart. They are also identified rather commonly by the compass directions which — as far as the usual diagram is concerned — reverse the familiar conventions of the map maker. Thus the ascendant is east, the descendant west, the nadir north and the midheaven south. According to tradition, the early astrologers thought that by reversing the geographical directions they would remind themselves that they were looking at the sky, with not altogether happy results. However, the primacy of the east as a point of origin in experience is properly emphasized by its present place, at least for people who read from left to right. The east-west axis, in terms of actual indication of direction, and quite apart from the method of representation on paper, is identical in astrology and geography, but the astrological north and south line is perpendicular to the surface of the earth, on which the geographic north and south are recognized. The midheaven, thus actually upward, lies towards the south for anyone north of the Tropic of Cancer, but this is a matter without astrological significance, and the designation is inept although well-entrenched in usage.

The Fourfold Rhythm of Reality

The two basic dichotomies, expressed in the house axes, have an equal rank in actual astrological practice. Although matters indicated by the horizon have a literal first importance in life, the meridian relations demand as much attention, and are concerned as fully in the development of the more detailed symbolism. What now must be understood is the manner in which the twofold division becomes, first, a functioning fourfold one, and secondly, a twelvefold classification of experience in astrology's very effective categories.

It should be clear that the original dichotomies are entirely overlapping, each creating two complete celestial hemispheres. When the double process is considered, either division may be the initial one, depending on the point of view, whereupon the completion of the other means, in practical fact, a halving of two hemispheres into four quarters. The separation between (1) upper or objective and (2) lower or subjective realms of experience, on the one hand, and between life as (3) initiated or controlled and (4) suffered or utilized, on the other, has only a limited significance, if the analysis does not proceed further. (2)

(2) A horoscope where the planets lie altogether in one of the four possible hemispheres is quite revealing astrologically, by that fact alone, and such charts have provided a simple case of interpretation for beginners in the author's earlier and smaller text of this series, How to Learn Astrology, Philadelphia, David McKay, 1941. However, not many nativities present this particular arrangement, and its indication is highly general.

Each of these possibilities properly makes a contribution to the other. Thus, when the universe is divided on the basis of the horizon, there is obviously a functioning intelligence which makes the division. The actual process of dividing represents a facing of life, or of its potentials, and so is fundamentally an expression of the second dichotomy, no matter how much the eastern outlook may be assumed or taken for granted. This means that the one process of hemisphering is really the bisection of a corresponding hemisphere which has already been established by the complementary and similar dichotomizing, and which is not now at the forefront of action, in this way:

In other words, the horizon at a is only completed over to b by projection, from the point of view of the meridian's hemisphere in which the horizontal division is taking place. The other half can be said to come into being, symbolically, by an operation of factors described at the descendant. There man leans or depends on things other than those of his own initiation or, in a very true sense, his facing of things has consequences. But the only way he can establish the whole horizon, actually, is by turning around, just as the baby does in a figurative fashion. When he is facing west, he has his back to the east, and so in counting on the fact that what he there described will remain as he has established it, at least until he can face east again. In a curious psychological way he gives this west the character of an east, momentarily, thus completing the horizon in the following fashion:

This is the all-important astrological principle of triangulation, now seen in its origin. When something divided into two is redivided in turn, the result is a quartering of the whole, but only two of such quarters are ever significant in relation to the previous division. If the hemispheres of first origin were both to be taken into account, when one of them is subdivided, their original definition would be destroyed or cancelled out, simply because a necessary unlikeness is lost. Referring again to the Genesis dichotomy, only one of the hemispheres participates in the subsequent evolution, namely, that claimed from the waters above. Actually any distinction in anything at all must substantiate a difference. Here is a necessity which underlies all logic. The idea is very clear when shown by diagram, figure A producing something which offers no significance to either pair of hemispheres but figure B making the eastern area quite distinct, and so accentuating a practical or actual difference between east and west.

Astrology, as a mathematical technique of analysis, reveals its logical foundation at this point. All four hemispheres are preserved, but no one of them is ever taken to be of any importance whatsoever except as it (1) ignores, in any special case, that half-universe from which it has been drawn apart, and (2) distributes instead the distinction between the hemispheres of the other and complementary dichotomy. The diagrammatic picture of the ascendant, in any horoscopic charting, would consequently take this form:

The indication of a is an activity of the east hemisphere, or the facing of things, as primarily a distinction between x or subjective impetus and y or objective conditioning. Thus a, x and y have a continual and special relationship at all times. The ascendant in horoscopy is the over-all indication of personality, and the particular personal equation in life which it represents (a) is always a constant balancing or teetering between inner or free impulses (x) and outer or compelled self-guidance (y), a proposition which will be amplified in detail. There are four ways in which the underlying rhythms of individual existence reveal their ramification throughout everyday living, and these are expressed, as far as the symbolism is concerned, in the following possibilities:

Here is diagrammatic preview are the four worlds of experience to which the next chapter is devoted. When these figures are interlaced, there is, in any given quarter of the whole circle, an emphasis of the basic hemisphere and a secondary influence of each hemisphere of which the quarter is not a part, as follows:

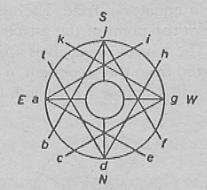

Taking all significance counterclockwise, the more usual direction of astrological relationship, a, emphasizes the east hemisphere per se, while b and c in order are the secondary influence of the south hemisphere in the east, and of the west hemisphere in the north. Meanwhile the primary east emphasis is completed at e in the north and i in the south, balancing the meridian-axis distinctions in terms of east. Similarly, d emphasizes north, with e and f the secondary influence of east in the north and south in the west, while the primary north emphasis is completed at h in the west and l in the east. The angle at g emphasizes west, with h and i the secondary influence of north in the west and east in the south, while the primary west emphasis is completed at k in the south and c in the north: Finally, j emphasizes south, with k and l the secondary influence of west in the south and north in the east, while the primary south emphasis is completed at b in the east and in the f west.

The origin of the houses, as well as the necessity for twelve of them, is thus disclosed on the diagrammatic side. Turning to the astronomical factor, three hundred and sixty degrees of motion in the heavens are divided into equal segments or mansions of thirty degrees, and the point at which each of such mansions begins is known as a CUSP. The houses following the hemisphere divisions or basic axes, counterclockwise, are angles, as already stated. The two other houses linked in each case with the angular one, in the manner shown, constitute, with that angle, an equatorial triad. Each of the four triads takes its name from the point of the astrological compass at which it is focal. The houses themselves are not named, but rather are numbered from the ascendant, a in the preceding diagram defining a first house, b a second, and so on.

In terms of these numbers, therefore, the fifth and ninth houses derive their meaning from the first, the eleventh and third from the seventh, the eighth and twelfth from the fourth, and the second and sixth from the tenth. The four mansions next counterclockwise from the angles in each instance are the SUCCEDENT houses — the second, fifth, eighth and eleventh — and the four behind the angles, from this point of view, are the CADENT ones — the third, sixth, ninth and twelfth.

The underlying relationship of the houses in the triads has its most simple expression in terms of time. The angles, at the focal points of the circle in a direct symbolization of the basic divisions of experience, have a present implication always. The succedent mansions indicate a future potential. The cadent ones chart factors of the past, or the influence of background and tradition in human relations. The idea of past or future in this connection, however, is not to be taken literally in the sense that anything pertinent is itself remote. Whatever is so designated is, rather, as it has relation to the present. This means some immediate activity of importance more conditioned, limited or endowed, as the case may be, through elements rooted in the remote. Obviously any non-immediacy in astrology is significant through its mediated pertinence. The fact that a man may inherit a large fortune in two years is not now vital beyond the degree to which this possibility has present implication, such as enabling him to borrow money, plan business, consummate marriage, and so on.

The outstanding value of astrology is its persistent emphasis on the reality at hand, that is, on the rhythms of life which may be used to sustain a real fulfillment of human hopes and ideas.

Astrology, How and Why it Works